Naturalization and Citizenship

Research Guides

About the Records

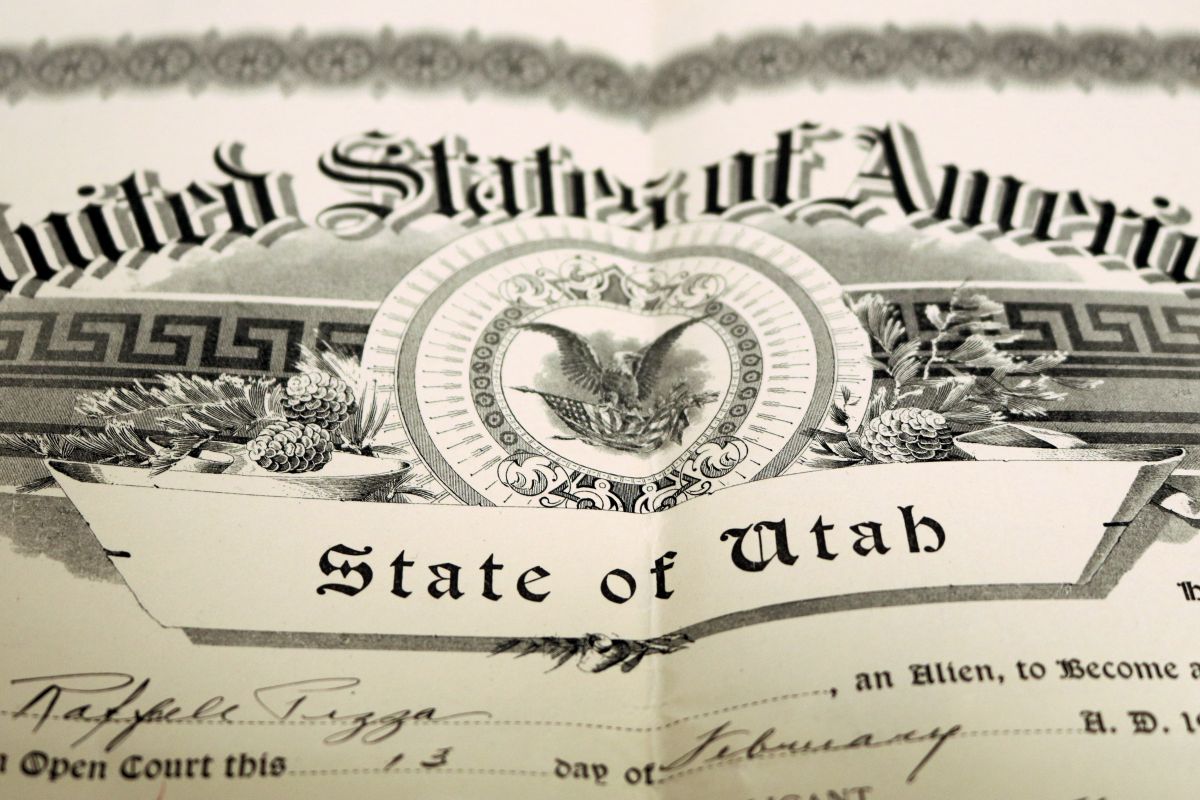

The Utah State Archives holds numerous older naturalization records. The naturalization process consisted of two parts: the Declaration of Intention and at least two years after the declaration, the Certificate of Citizenship. Naturalization moved beyond state courts and became an entirely federal process by the middle of the 20th century.

Before 1906

Federal law outlined the naturalization process, but individual courts dictated many of the specifics. An individual could make the Declaration of Intention at any court in the nation; not necessarily to a court in his place of residence (only single women naturalized on their own before 1922). The form varied somewhat from court to court but generally it provides only minimal information: the individual's name, country of origin, and the names of two witnesses.

The individual could apply for citizenship two years later provided he had been a U.S. resident for five years and was a resident of the state or territory where the court was located for at least one year. There was no upper time limit to apply for citizenship. Those who had come to the U.S. as minors (whose parents were not naturalized) did not have to file a prior declaration of intention. At the citizenship hearing, the resident alien renounced his allegiance to his home country, witnesses swore to his worthiness of becoming a citizen, and he took an oath to the United States. The court issued a certificate of citizenship to the successful candidate indicating his name, country of origin, witnesses' names, and his sworn fidelity to the United States.

If an individual completed either part or all of this process in Utah, there are many courts to check prior to statehood (1896). Each county had a County Probate Court until 1896. There are also District Courts which served multiple counties. Furthermore, district court boundaries changed over time, so check the records of several district courts. The Utah Supreme Court's records should also be consulted. If the residence of the individual is known, it is possible he filed in the most geographically convenient court, but there was no legal requirement to do so.

After 1906

In 1906 the federal Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (now U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) standardized naturalization procedures. This included providing the same forms for all the courts to use. These contain much more information than the earlier records. The declaration and naturalization forms not only include name and country of origin, but often age, occupation, marital status, immigration information, names of children, etc.

At this time, the individual was required by law to file with the court having jurisdiction over the area in which he lived, not just in any court in the country. The time frame was also narrowed. An individual had to declare his intent to become a citizen at least two years prior to applying for citizenship, but he could only apply for citizenship within seven years after the declaration. Therefore, checking for a Declaration of Intention first can narrow the search for the exact date of naturalization to five years.

Naturalization records are available from many Utah district courts up to the middle of the twentieth century. However, all naturalization records since 1906 have copies available from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. A Genealogy Program handles requests for historical records dated from 1893 to about 1956. An index exists and may be searched for a fee. Requests for searches and copies of documents are made by mail or online.

For naturalization records after 1956, submit a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to:

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

National Records Center, FOIA/PA Office

P. O. Box 648010

Lee’s Summit, MO 64064-8010

If the individual was born more than 100 years ago however, the National Archives may have naturalization "Alien Files" created after 1956 as part of an ongoing transfer process.

Finally, if the individual was naturalized very recently, one may be able to request a Replacement Naturalization/Citizenship Document from USCIS. Submit Form N-565 which is available online at www.uscis.gov/n-565.

Exclusions and Exceptions

Various minority groups (e.g., Chinese, Blacks, Native Americans, Hawaiians) or immigration sources (such as Southern Europe) may not have been permitted citizenship, especially starting later in the 19th century. Though at times veterans were allowed to waive parts of the process or wait less time.

- 1882 - Chinese Exclusion Act, which would be extended in some form until 1902 (22 Stat. 58).

1891 - Classes of persons denied the right to immigrate to the U.S.—insane, paupers, persons with contagious diseases, persons convicted of felonies or misdemeanors of moral turpitude, and polygamists (26 Stat. 1084) - 1900 - Hawaii Organic Act, granting U.S. citizenship to residents on or before August 12, 1898 (31 Stat. 141).

- 1921 - Quota Act limiting immigration from each country based on population in 1910 Census (42 Stat. 5).

- 1924 - Immigration Act with more limits, especially from Southern and Eastern Europe, plus Middle Easterners, East Asians, and Asian Indians (43 Stat. 153).

- 1924 - Indian Citizenship Act, granting citizenship to all Native Americans born within the borders of the United States (43 Stat. 253).

- 1965 - "National quotas" replaced with "annual ceilings" for number of immigrants, strongly relying on family relationships for granting requisite visas for immigration (9 Stat. 911).

Women and Children

From 1855 to 1922, a married woman automatically assumed the citizenship of her husband; if an American woman married a foreign national, she lost her U.S. citizenship. Similarly, if a foreign national married a U.S. citizen, she automatically became a citizen. Her only documentation would be her marriage license and the naturalization (or birth) record of her husband.

With the passage of the Cable Act in 1922, women were allowed to naturalize on their own (42 Stat. 1021). A married woman whose husband was a citizen did not need to file a Declaration of Intent. A woman who had lost her citizenship through marriage and regained it under the Cable Act could file to naturalize in any naturalization court. In 1936, Congress passed a new act allowing a woman who had lost her citizenship between 1907-1922 through marriage to a foreign national to take an oath of allegiance for citizenship to be restored.

From 1790 to 1940 children under the age of 21 automatically assumed citizenship with the naturalization of their father. Before 1906 names of minor children rarely appeared on the declaration or petition forms. If there was no father who could naturalize himself and his family, a minor alien who had lived in the U.S. for at least five years could file the declaration and petition together before his 23rd birthday.

In 1929, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service began issuing a “Certificate of Derivative Citizenship” to women and children who had gained naturalization through the naturalization of their husband or father.

State Archives Holdings

The following are the principal naturalization holdings of the Utah State Archives. Record books include a full transcription of the declaration or naturalization record and are thus the most informative.

Aside from the Utah State Archives, other records may still be held by the court or have been transferred to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. The Rocky Mountain branch of the National Archives holds some naturalization records for Second District Court: Weber County (ca. 1907-1913; 1930-), Third District Court: Salt Lake County (ca. 1930-), and Fourth District Court: Utah County (ca. 1939-), as well as some federal district court naturalization records from Utah.

Sources and Further Reading

Page Last Updated September 19, 2024.

About this Guide

Originally published before 1999, with revisions by Gina Strack in 2007 and Heidi Stringham in 2015.