Mining Records

Research Guides

About the Records

Mining is an important part of Utah's economic development. Utah county recorders and mining district recorders kept numerous documents associated with individual mining claims. The Utah State Archives holds a large number of such records, mostly from the territorial period.

Mining Districts

Prior to statehood, mining records were usually kept by mining district recorders.

Records and Record Types

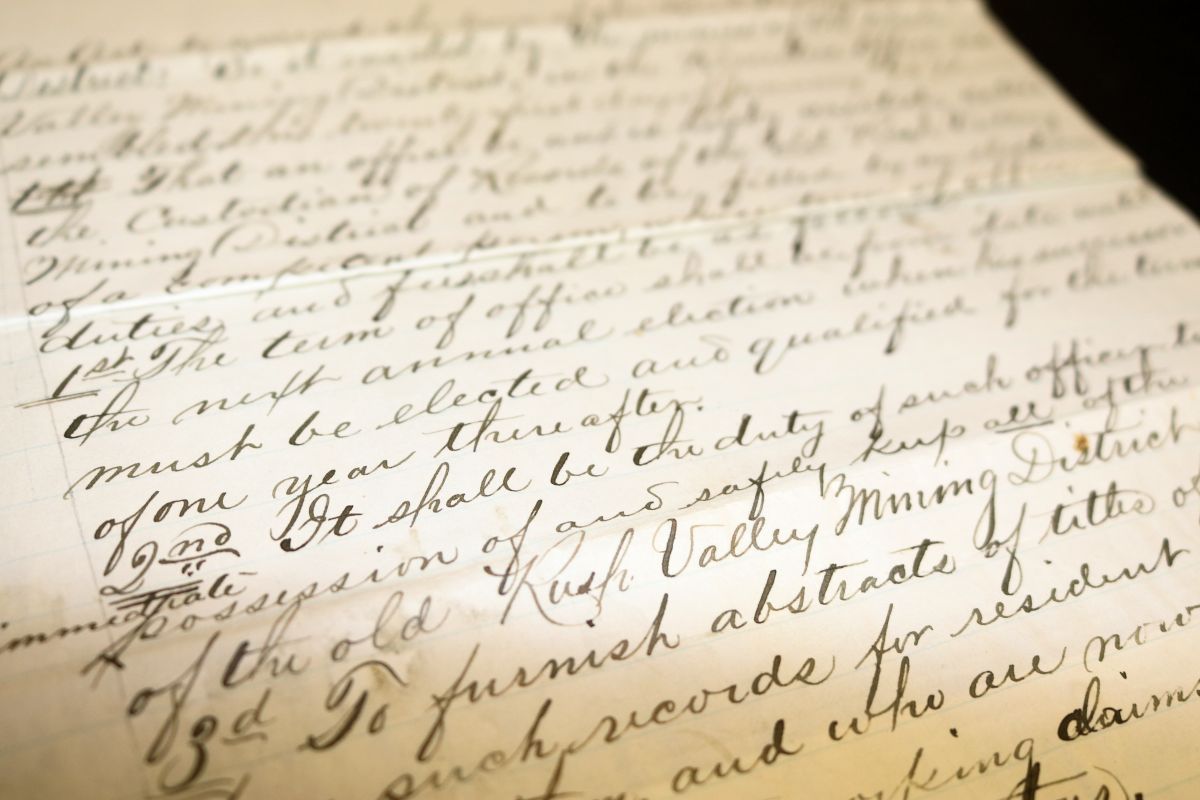

Documents associated with mining claims include the by-laws of various mining districts. They include thousands of individual notices of location, as well as mining deeds, affidavits showing proof of annual assessment labor, notices of intent to hold a claim, and lease documents. Mining district and county recorders have also created indexes and abstracts to enable the retrieval of these documents.

Notices of Location

A document that records a specific claim is called a notice of location. In 1866 Congress authorized the location of a lode throughout its depth, but not the location of the land encompassing the deposit, but in 1870 extended rights to "placer claims," allowing prospectors to claim up to 160 acres. Congress adopted a fully developed mining law in 1872. This law continued the policy of making mineral deposits free and open to exploration and purchase according to the rules of local mining districts, but added certain regulations. Claims were limited to 1500 feet along a vein or lode with no more than 300 feet on either side of the center, and placer claims were limited to 20 acres. After statehood, the Utah Legislature added certain qualifications to the federal law. Utah locators were required to mark their claims according to detailed instructions and to have a notice of location recorded by the county recorder within thirty days.

The 1872 mining law limited claims to "valuable" deposits. The issue of whether or not this law applied to petroleum became especially hot in the 1890s. In 1896 the General Land Office determined that petroleum was not "locatable." The following year (1897), Congress clarified the dispute by passing the Oil Placer Act, which stated that oil and gas were locatable under the general mining law. While most location notices recorded during the territorial period were recorded by prospectors searching for precious metals, many petroleum locations were recorded in the early twentieth century.

Notices of location dominate the mining records kept by both mining district and county recorders. Many thousands of them have been recorded. Each notice identifies the claim by a unique name, such as "Poor Man's Friend," "Sunshine Lode," "Bald Eagle Mine," or "Good Luck Mine." Each notice names the locators, indicates the date of location, and tells how many feet or acres the claim involves. Location notices confirm compliance with federal law and affirm the locator's citizenship. They indicate whether the claim is a lode or placer claim and sometimes name the valuable mineral being sought. Books of location notices also contain variations such as location amendments, relocation notices, or location notices for water or mill sites used in mining activities.

Proof of Labor

The General Mining Law of 1872 added a requirement for at least $100 worth of annual assessment work to be done on each claim in order to maintain it. Failure to mark and record a claim or to do the necessary annual assessment work would open the claim for location by someone else. County or mining district recorders kept track of this assessment work. In affidavits showing proof of labor, a claimant swore that he had performed the necessary amount of labor and usually specified exactly what that labor involved, who did the work, and when. Some mining districts required district recorders to personally examine work done and make their own assessment. As long as claims were properly recorded and maintained through annual assessment work, locators could continue to hold them without the necessity of any record except at the local level. After statehood, the Utah Legislature passed a law requiring prospectors to do at least $50 worth of labor within the first ninety days and specifying details required in affidavits showing proof of labor filed thereafter.

Mining Deeds

A revision of the 1872 Mining Law provided a process by which claims could be patented (owned outright). Anyone who had properly located a claim could file a patent application. The application was to be accompanied by a plat map and field notes made or authorized by the surveyor general and two affidavits verifying that the claim had been distinctly marked at the site and that notice of patent application had been posted. Applicants were additionally required to do at least $500 worth of labor on the claim and prove that no adverse claims had been filed. After these requirements had been met, the applicant could purchase the mineral land for $5 an acre. A mineral certificate issued by the district land office entitled the claimant to a federal patent.

Utah county recorders kept copies of patents and mineral certificates with other mining deeds, which by definition, transfer interest in mining claims or ownership of mineral lands from one party to another. Mining deeds name a grantor (giver) and grantee (recipient), specify the amount of consideration money, and indicate whether divided or undivided interest in the claim. They describe the location of the claim and identify when, where, and by whom it was originally recorded. Most district or county recorders kept mining deeds separate from location notices. Often they are intermingled with other deeds transferring land.

Intent to hold a claim

Congress suspended the annual assessment requirement during some recession years, especially during World War I, and the 1930s. While claim holders were not required to perform annual assessment work during these years, the law required that each miner file an intention to hold a claim.

Lease documents

In 1920, Congress made a major departure from the original location system. The Mineral Leasing Act rescinded the right to locate and mine fossil fuel and chemical minerals and replaced the location system with a permit and leasing system. This 1920 law authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue prospecting permits and leases for the development of gas, oil, phosphates, and coal. Qualified applicants could obtain prospecting permits allowing exclusive rights to explore up to 2,560 acres. The permit holder could lease up to 640 acres if oil was discovered. Leaseholders are required to pay rent and royalties of not less than 12 % of the production value. Similar regulations were put in place for gas, coal, and phosphates. Utah county recorders' books contain numerous notices of location for petroleum in the early 1900s. After 1920 these claims were replaced by leases and agreements.

Indexes and abstracts

County recorders created various indexes and abstracts to provide reference to the notices of location and other mining records. Indexes usually identify the claim, the kind of document, the date, names of locators, and the book and page number where documents were recorded. Abstracts begin with a notice of location and chronologically list each document associated with a claim. They indicate where relevant documents were recorded. Most early indexes and abstracts provide reference based on the name of the mine or claim but not the names of the individuals or corporations involved.

Sources

"An Act granting the Right of Way to Ditch and Canal Owners over the Public Lands, and for other Purposes" (July 26, 1866). The Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations, of the United States of America, vol. XIV. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1868.

"An Act Providing for the Manner of Locating and Recording Quartz and Placer Mining Claims" (March 11, 1897). Laws of Utah, 1897.

"An Act Providing for the suspension of annual assessment work on mining claims held by location in the United States and Alaska" (May 18, 1933; May 15, 1934). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. 48, part 1. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1934.

"An Act to authorize the entry and patenting of lands containing petroleum and other mineral oils under the placer-mining laws of the United States" (February 11, 1897). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. 29. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897.

"An Act to promote the Development of the Mining Resources of the United States" (May 10, 1872). The Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamations, of the United States of America, vol. XIV. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1873.

"An Act to promote the mining of coal, phosphate, oil, oil shale, gas, and sodium on the public domain" (February 25, 1920). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. 41, part 1. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1921.

Butler, B.S., G.F. Loughlin, V.C. Heikes and others. The Ore Deposits of Utah. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1920.

Copp, Henry Norris. Manual for the use of Prospectors on the Mineral Lands of the United States. 1897. Reprint. New York: Arno Press, 1979.

"Joint Resolution To suspend the requirements of annual assessment work on mining claims during the years 1917 and 1918" (October 5, 1917). The Statutes at Large of the United States of America, vol. 40, part 1. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1919.

Mall, Loren L. Public Land and Mining Law, text and cases. Seattle, Wash: Butterworth (Legal Publishers), c1981.

Revised Statutes of the United States. 43rd Congress, 1873-1875, Chapter Six, "Mineral Lands and Mining Resources."

Utah Mining Association. Utah's Mining Industry; an Historical, Operational, and Economic Review of Utah's Mining Industry. 1967.

Page Last Updated June 12, 2003.

About this Guide

Written by Rosemary Cundiff and originally published in August 2002.