A Monumental Controversy

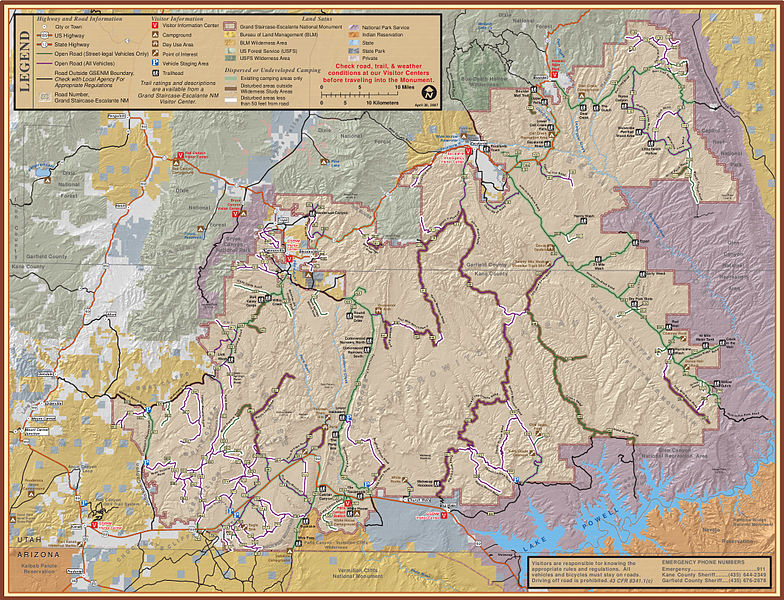

In September 1996, President Bill Clinton made the controversial decision to draw on powers reserved to him by the 1906 Antiquities Act, and designate 1,880,461 aces of land in southern Utah as the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. But did you know that sixty years earlier federal officials were pondering the designation of a similar monument that would have dwarfed the area covered by today’s Grand Staircase?

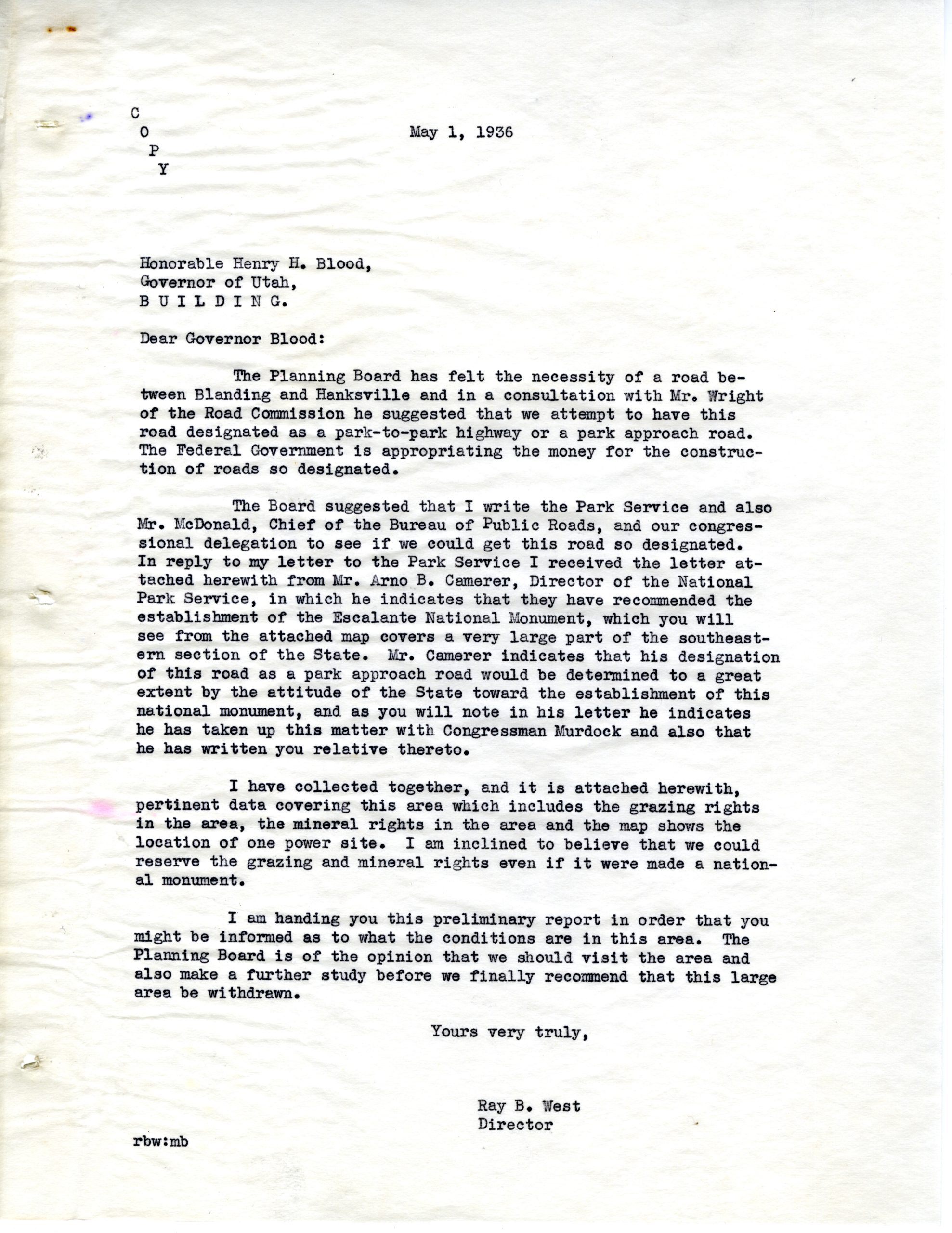

The story begins in 1936 when Utah State Planning Board Director, Ray B. West contacted assistant director of the National Park Service (NPS), A.E. Demaray about the possibility of the service building a federal park-to-park highway linking the remote southern Utah towns of Hanksville and Blanding. West’s contention was that this highway would serve a vital role in connecting Mesa Verde National Park to the proposed Wayne Wonderland area in central Utah (an area that would later become Capitol Reef National Park).

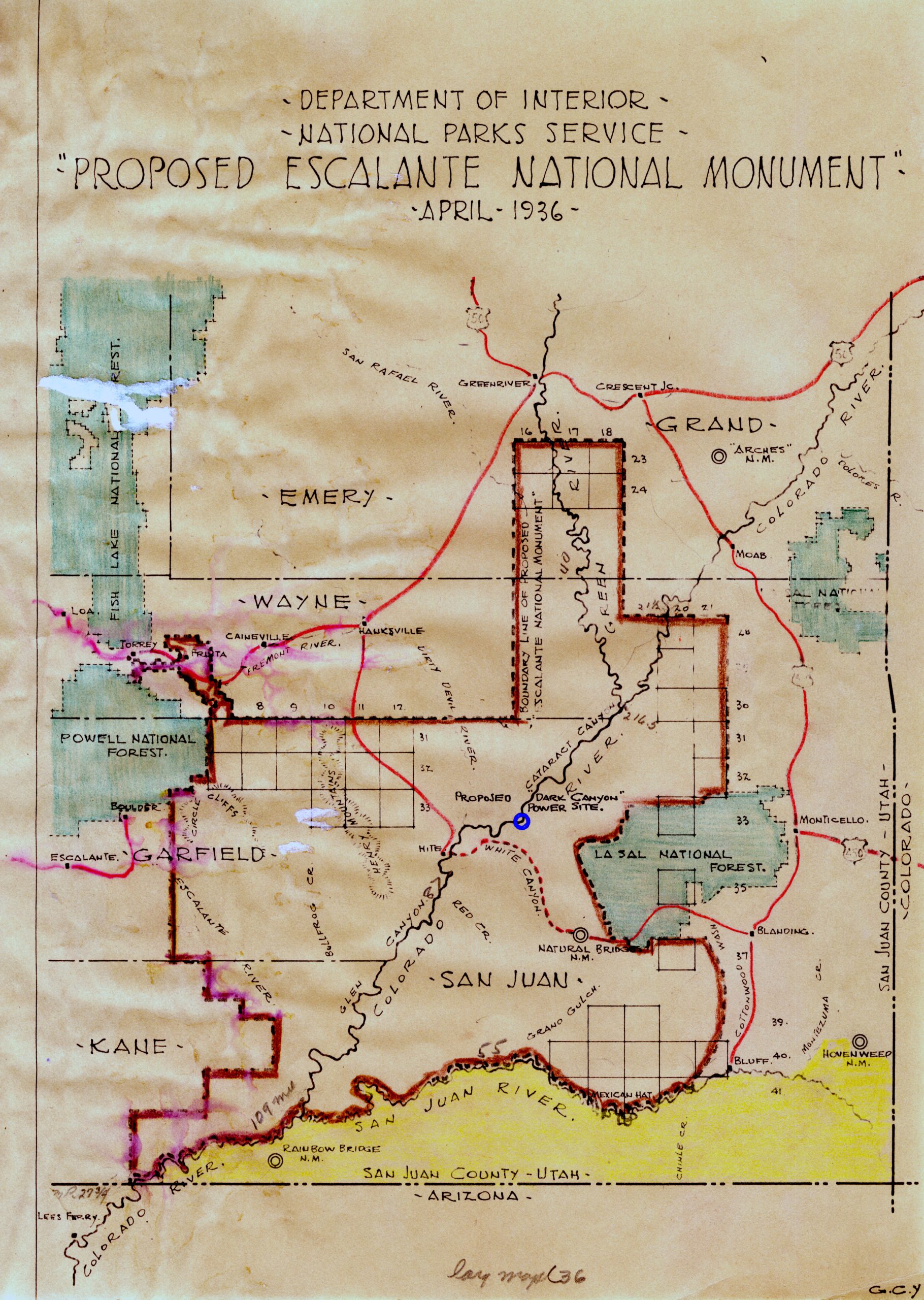

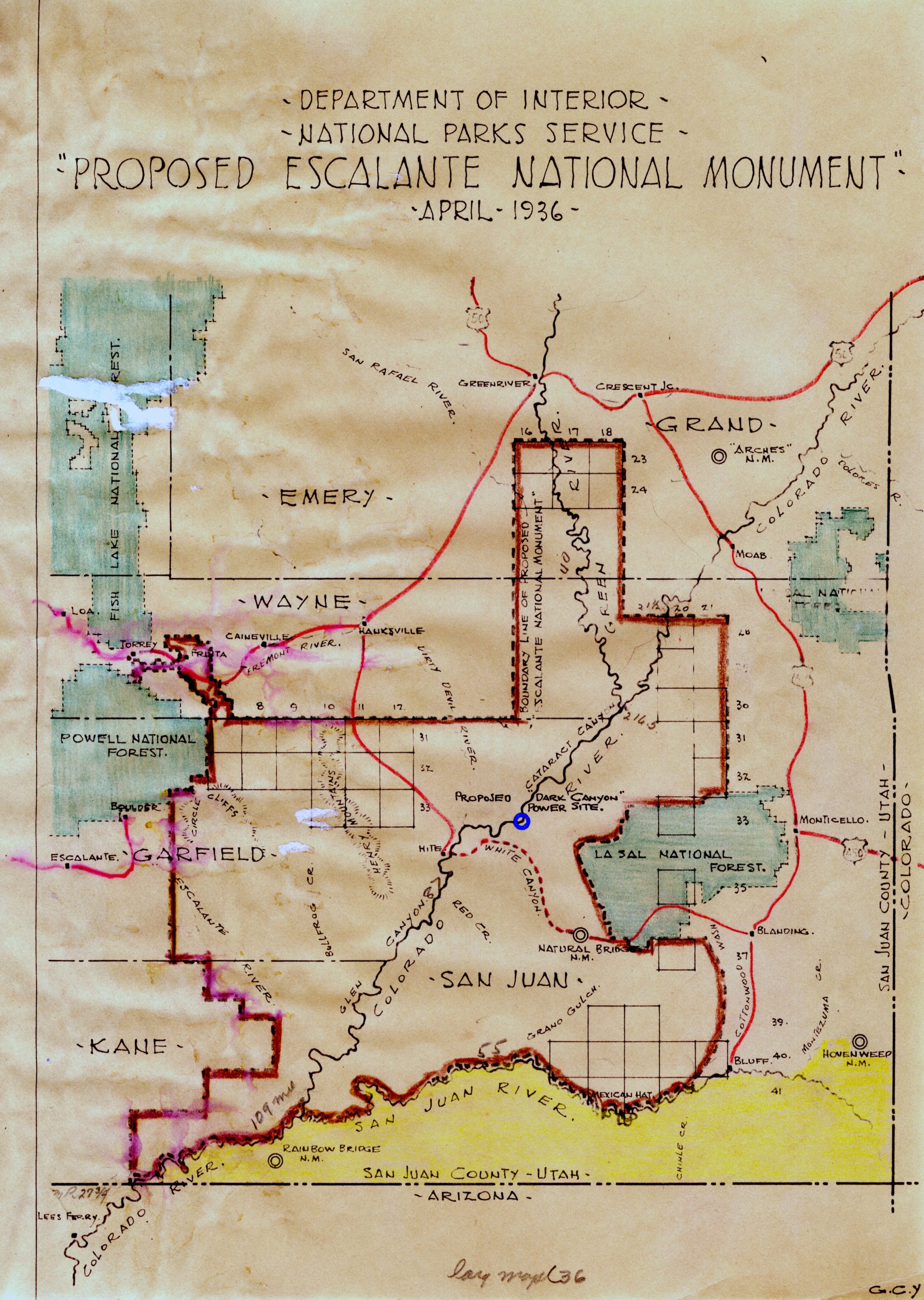

A response to West’s letter came from NPS director Arno Cammerer, who stated that the agency was considering making a recommendation to President Franklin Roosevelt to designate an enormous section of the state as a new “Escalante National Monument.” Cammerer further intimated to West that the Hanksville-to-Blanding road he had requested would face better odds of being completed if Utah government officials were willing to support the NPS proposal.

The 1936 NPS proposal was staggering in its scope, taking in 6,968 square miles of southern Utah land (approximately 8% of the state). Almost immediately the State Planning Board undertook a study, at the request of Utah Governor Henry Blood, to determine how monument designation might impact Utah’s grazing, mineral, and water rights along the Colorado River.

Debate over the proposed monument became a hot topic in the state in the ensuing years. A December 1938 article in the Iron County Record spells out the concerns voiced by both sides, stating:

“The opposition maintains that the establishment of the monument would infringe on grazing rights, and would close the door to possible Colorado river developments for irrigation, flood control, and power development, etc., while those favoring the project maintain that the area has no grazing value, that irrigation would not only be impracticable, but impossible, and that the upper stretches of the Colorado and Green rivers afford much better flood control, irrigation, and power development possibilities.”

Opposition to the monument proposal grew in Utah, and in 1938 the parks service put out a second proposal for the monument, scaling dramatically back on its original size. This new monument would claim approximately 2,450 square miles of land along the Colorado River.

When the second park proposal was met with resistance from Utah officials, NPS administrators and Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, changed course. Federal agents backed off the idea of having President Roosevelt unilaterally claim the region as a national monument, and instead proposed that the U.S. Congress designate it a national recreation area. Under such a designation, the state of Utah would have maintained many of the development rights over natural resources, which had served as the greatest source of concern for state officials. Ultimately, however, the bill to create the Escalante National Recreation Area never made it out of congressional committee.

This episode is played out in records held by the Utah State Archives from both the Utah Planning Board, as well as Utah Governor Henry Blood. As historian Sam Schmieding points out in his administrative history of Canyonlands National Park, “the failed Escalante proposals and conservationism’s discovery of canyon country dramatically altered the historical context and dynamics of scarcity that would influence how the National Park Service and American society classified and valued canyon country in the future.” In effect, this moment in Utah’s history reflects many of the ongoing issues between state and federal officials over federally held land in the state. It also helps us better understand the difficult nature of balancing the twin interests of preservation and resource development in Utah’s spectacular canyon country.

Recent Posts

From Pews to Pixels: Weber State’s Stewart Library Digitizes New Zion Baptist Church’s Legacy

New Finding Aids at the Archives: March 2024

Sealing the Deal: Tooele County Clerk’s Office Unlocks the Vault with Historic Marriage Records

Summer 2024 Internships

Developing History: Park City Museum’s Snapshot into the Past

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/