Poll taxes in Utah?

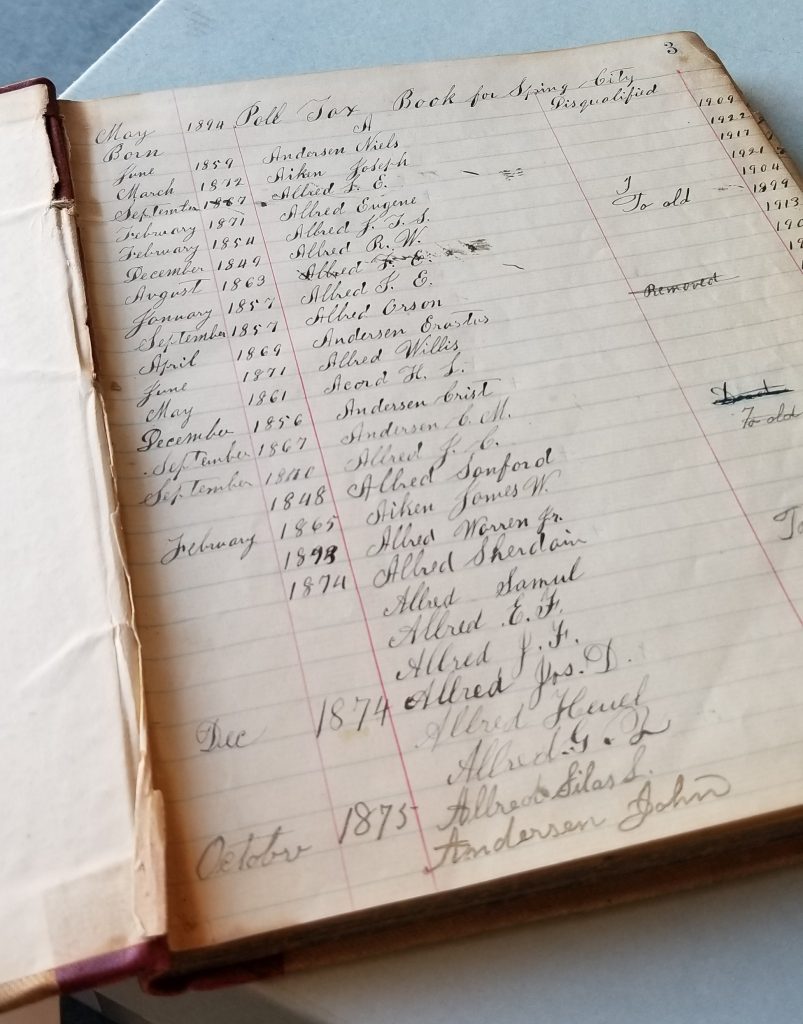

Poll taxes, or fixed sums levied on any eligible individual, are uncommon these days. Historically, they are usually discussed in conjunction with civil rights and disenfranchisement. So it might be a bit surprising to come across a record like this, a poll tax register from Spring City. We often hear about poll taxes in the Deep South, but here in Utah? Let’s take a deeper look.

This poll tax ledger from Spring City came to us in May 2019 with the transfer of a large volume of historic records from the city. This record, along with others transferred at the time, has now been fully processed, cataloged, and preserved. Archives staff are choosing particularly intriguing examples from the collection to share on our blog and highlight the city’s rich history and our partnership with the community in the process of this transfer.

Poll taxes are also known as “head taxes” or “capitations.” Historically, these taxes were introduced in the Middle Ages as a way to earn governing bodies money (usually to fund wars). “Poll” came from a Low German word meaning head and when first used in conjunction with taxation, had nothing to do with the right to vote. Instead, “polling” in a voting context, usually referring to one vote per person, came about in the mid-1600s and was borne of the same etymological background as “poll” meaning head. In colonial North America, poll taxes were common. For example, in Massachusetts, they accounted for one-third to one-half of the colony’s tax revenue.

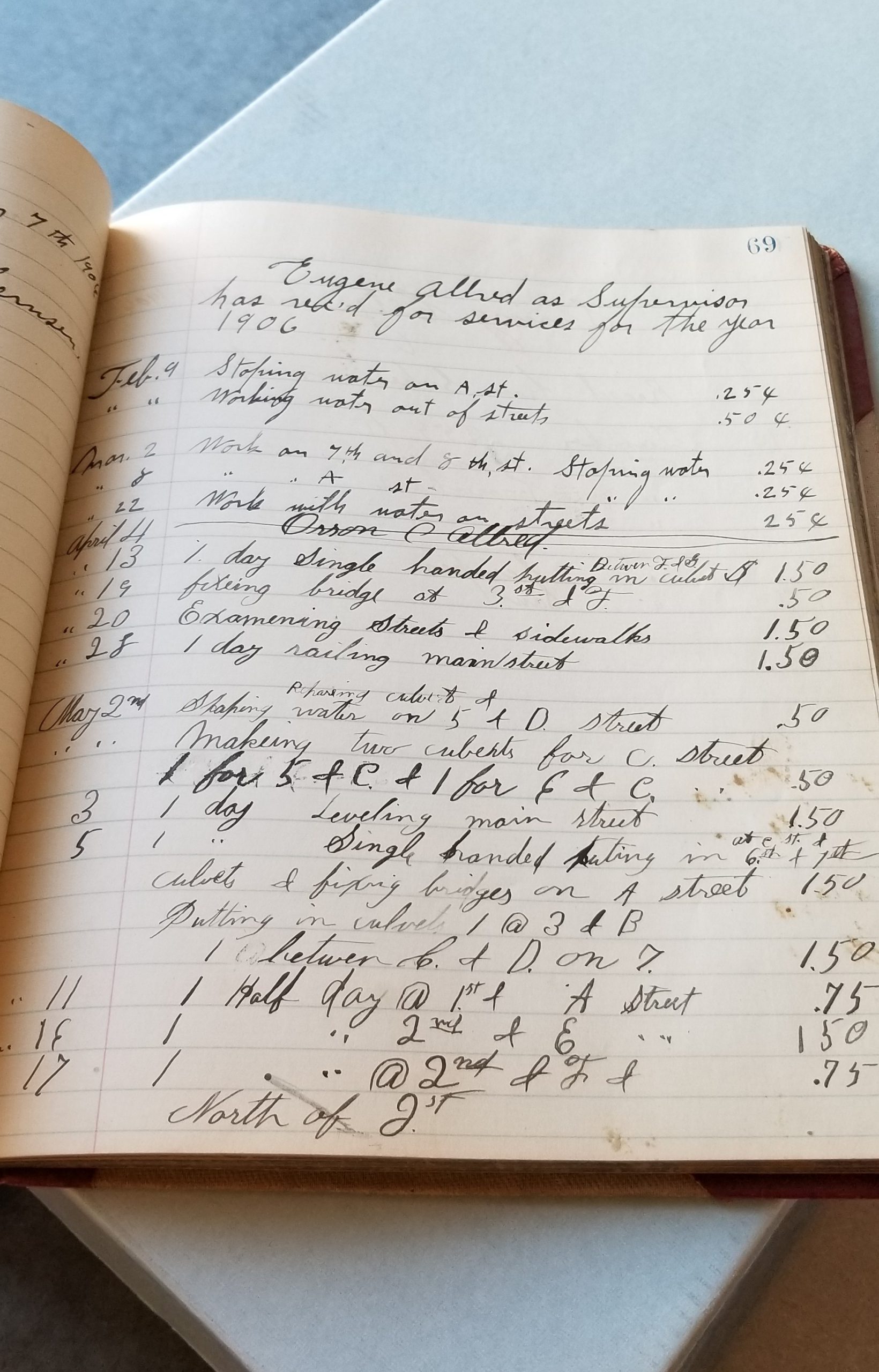

Traditionally, poll taxes are regressive, meaning that everyone, no matter their income or the value of their assets, is taxed a fixed sum. Regressive taxes usually place undue burden on the lowest earners in any society. Utah’s state legislature allowed for poll taxes to be levied in order to pay for roads. State law counted male residents between the ages of 16-50 as eligible for taxation. If the tax was not paid, the men could work for two days on road building projects. If neither payment nor work was accounted for, the state or local entity levying the taxes could collect on wages or property by suit.

Though allowed by the state’s constitution, poll taxes were largely unpopular amongst Utahns. A newspaper article in the Manti Messenger in 1897 argued that residents were not seeing the results of their taxes. “If an amount in money equal to the amount annually expended in labor were devoted to road building, there would be a vast difference. Service under the existing law is poorly rendered, and grudgingly at that,” the paper argued.

While never popular, poll taxes garnered a particularly poor reputation after the way they were used to deny basic rights to American citizens through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, up to the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.

With the end of the Civil War came the 15th Amendment stating that, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This Amendment effectively gave black Americans the right to vote. However, fierce backlash arose throughout the country, notably (though not solely) in the former Confederate states of the South. While freed black Americans could not be denied the right to vote based on the color of their skin or their former status as enslaved people, many states found a way around this Amendment by instituting the requirement that all qualified voters pay a poll tax before they could cast their ballots. As many formerly enslaved Americans struggled to find jobs and earn steady incomes, they often found themselves denied the funds that would have enabled them to pay such poll taxes, and thus their constitutional rights were circumvented and they were legally barred from voting.

It wasn’t until a combination of the 24th Amendment in 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and a handful of Supreme Court decisions in 1965-1966 that poll taxes were finally abolished in the United States and could no longer be used to disenfranchise minorities or the poor.

Payment of Utah’s poll taxes were never used as a prerequisite for voting and therefore aren’t quite the same as poll taxes we might recall hearing about in our high school history classes. Nevertheless, they were unpopular. In 1911, Judge A.N. Cherry of Gunnison, Utah published an editorial against poll taxes, proposing that they be replaced instead with property taxes. This idea was gaining hold throughout the country at the time, particularly as settlers moved West and land was considered more valuable. Early 1915 saw the issue of poll taxes rise to the level of the state Supreme Court. The taxes were ruled constitutionally valid, but they still remained strongly disliked by the populace. By 1919, the state legislature had abolished the poll tax. “While the law has done a great deal of good in the past by helping to build our roads, it has served its purpose,” the Manti Messenger reported on the move.

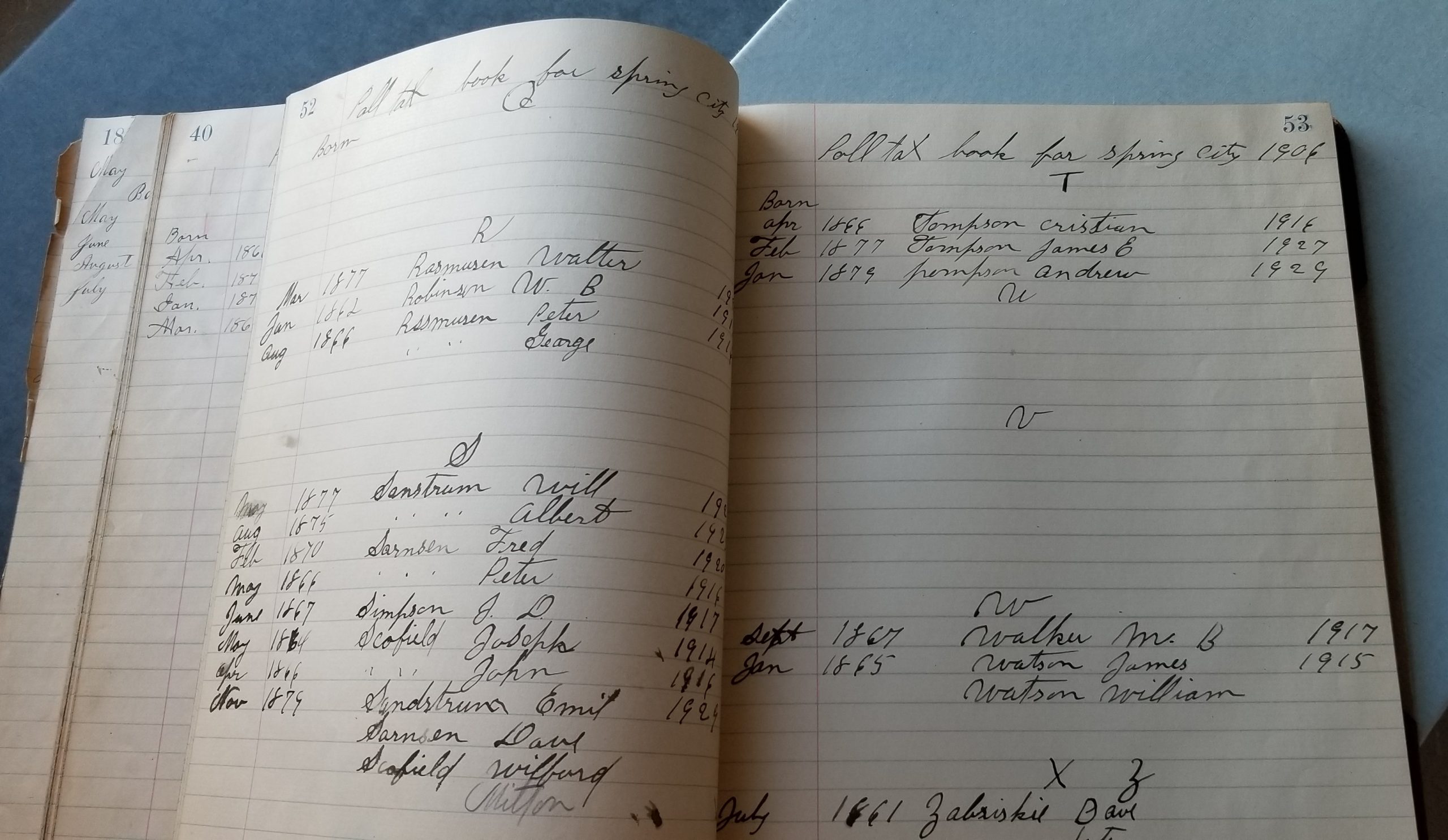

These ledgers contain information such as the names of Spring City residents (male only), their birth month and year, the year they would age out of eligibility for paying poll taxes, and, if applicable, a brief explanation of why a resident may be exempt from paying.

Recent Posts

Authors

Categories

- Certification/

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- FAQ/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- GRAMA FAQs/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Hub/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- RIM FAQs/

- Roles and Responsibilities/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/