The Great Salt Fake

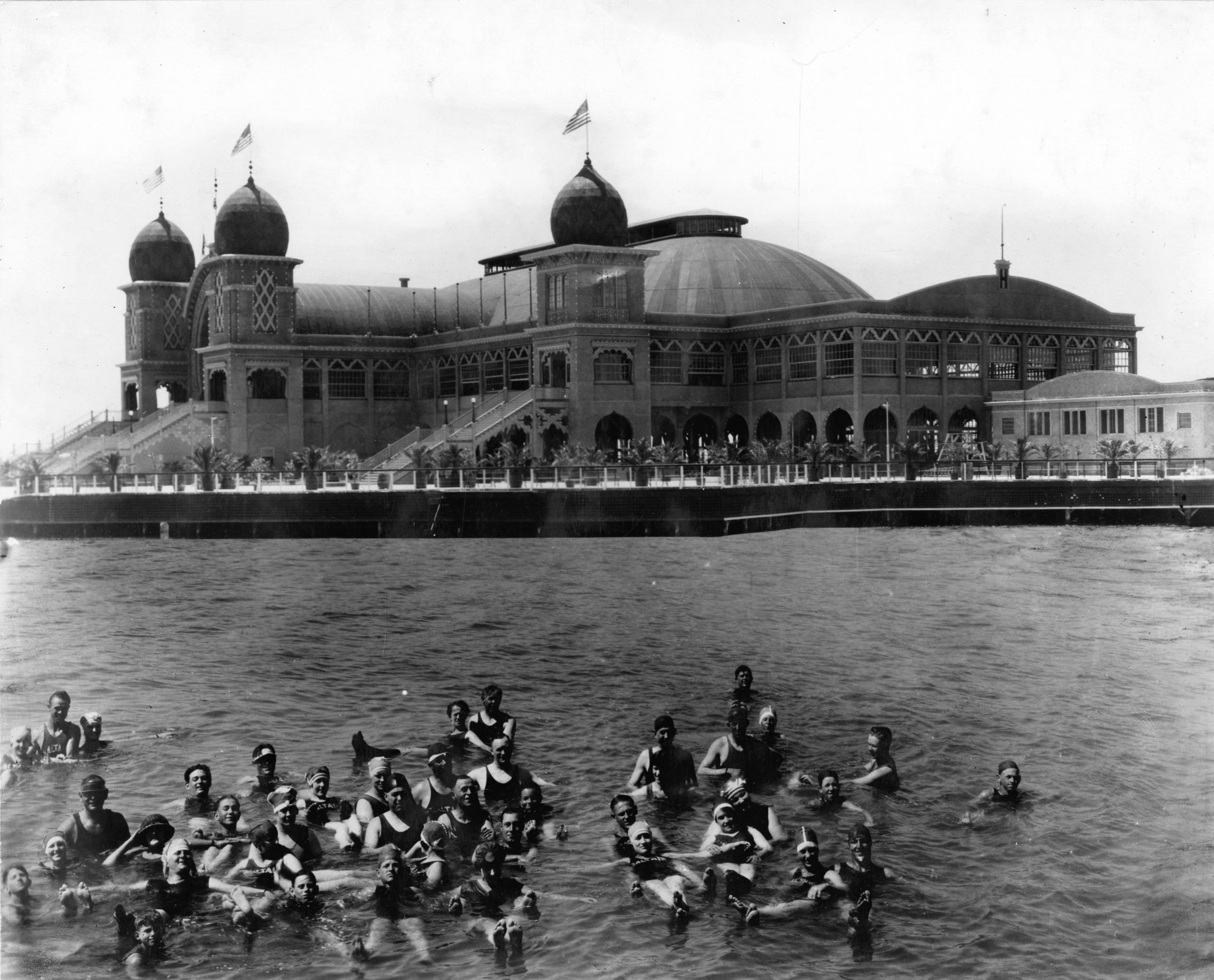

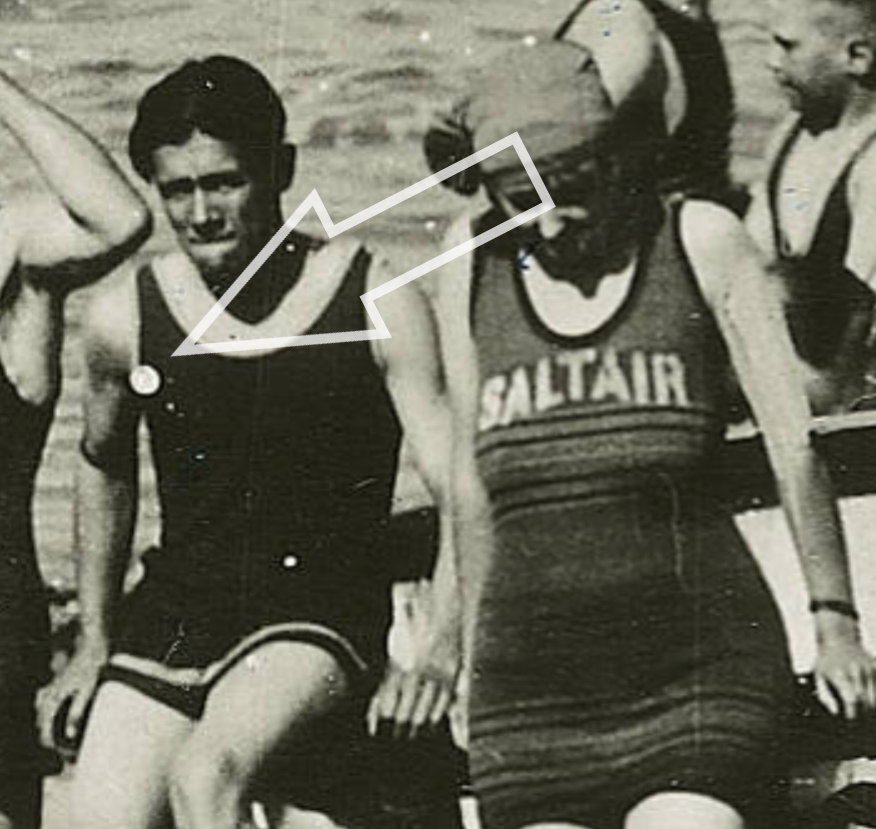

A copy of a black and white photo of the Saltair sits above my Grandma’s desk. I’ve been obsessed with it since I was a kid. Her father claimed to be one of the bathers featured in the center of the picture perched upon a floating tub. He’s surrounded by a group of men and women, frolicking in their old-timey swimsuits floating in front of the ornate pavilion. Being featured in this photograph was my great-grandpa’s claim to fame. He had good reason to be proud; it is an impressive image that captures a compelling visual history. One of those “I can’t believe you were there” envy-inducing kinds of photographs. It’s no wonder it is one of the most used pictures of the Great Saltair; featured today on restaurant walls, postcards, and souvenir boxes of saltwater taffy. It is a marvel that one picture so perfectly captures such a unique moment in Utah history. Of course, it could be because this photo was intentionally designed to do just that. Like many of the cropped and filtered photos I scroll past on my Instagram feed, this particular picture is a clever edit and a bit of skillful photo fakery.

This famous image is a composite of two real photographs; one of Saltair bathers (likely taken from the deck of the pavilion looking out toward the Great Salt Lake), and one of the pavilion taken from a platform on the lake. While the image we are familiar with of the floating swimmers posed in front of the famed pavilion didn’t actually occur as pictured, it is still a work of art in its own right, carefully crafted for a unique purpose by a skillful designer who manually worked in detail with meticulous accuracy.

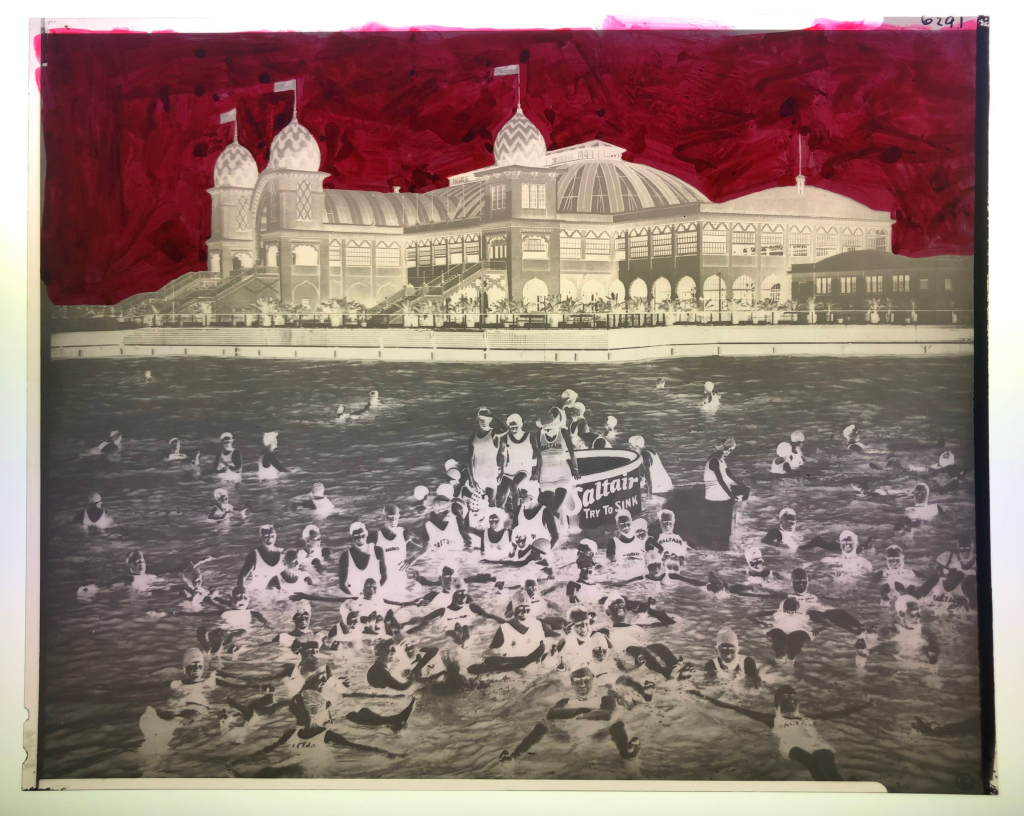

Once you are aware that the image is a composite of two real photographs, you can begin to see the subtle lines indicating where the two photos were cut and spliced together. Composite images were a standard photo editing practice in the early days of photography. Photographers often created composites of the correct exposures to clarify the picture’s foreground and background subjects. The creator of this Saltair composite may not have been able to take a photo of both the floating swimmers and the pavilion and get the proper exposure for each subject simultaneously; a composite may have made the most sense for the image they needed to create. A composite designer would have to consider many details to make a convincing image, including ensuring shadows and light from two separate photographs matched in both foreground and background and that the proportions of the combined pictures were to scale.

In this composite of the Saltair, the creator pasted together three different strips from the two source pictures to form the single image. One image of the pavilion down to the dock, one thin strip of the lake added just below the deck and above the heads of the swimmers, and of course, one of the floating swimmers. The thin strip between the larger two images was likely added to create depth between the subjects and ensure the foreground’s swimmers were to scale with the large building in the background.

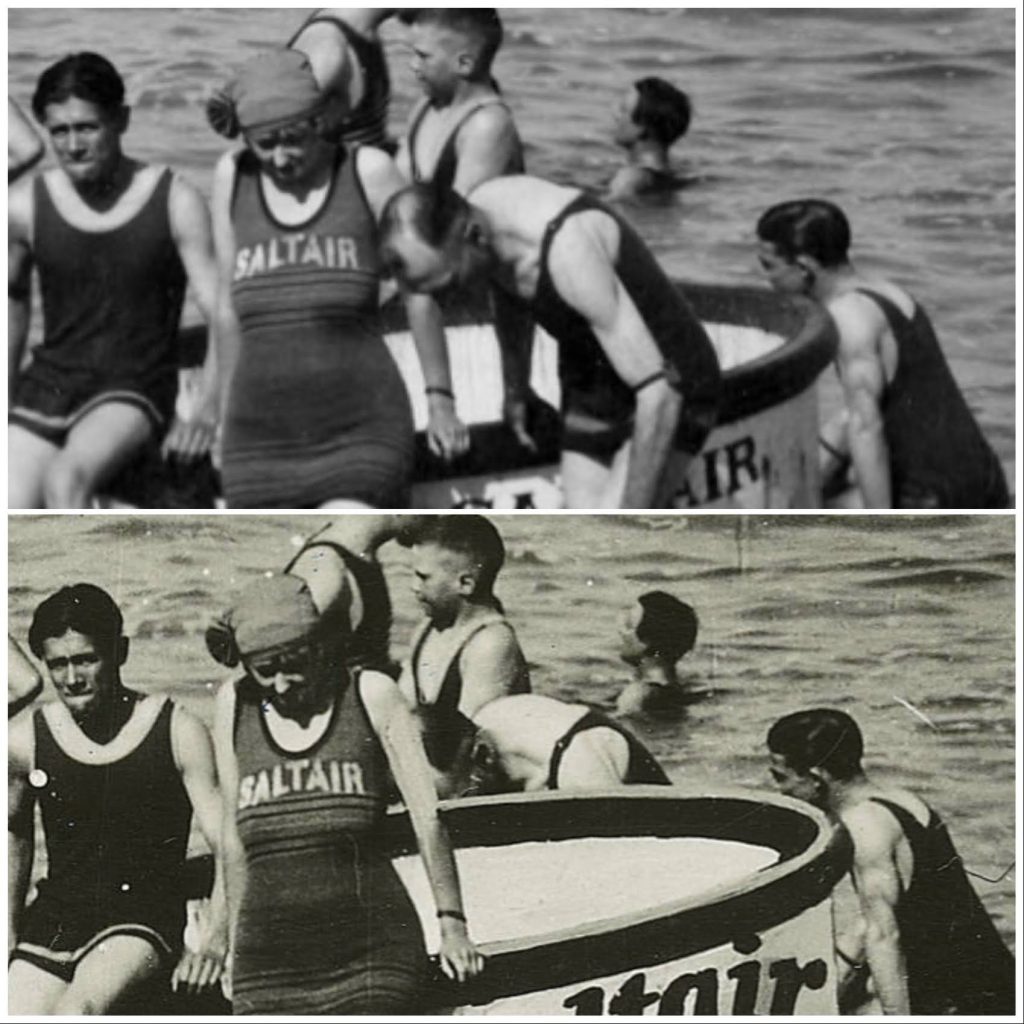

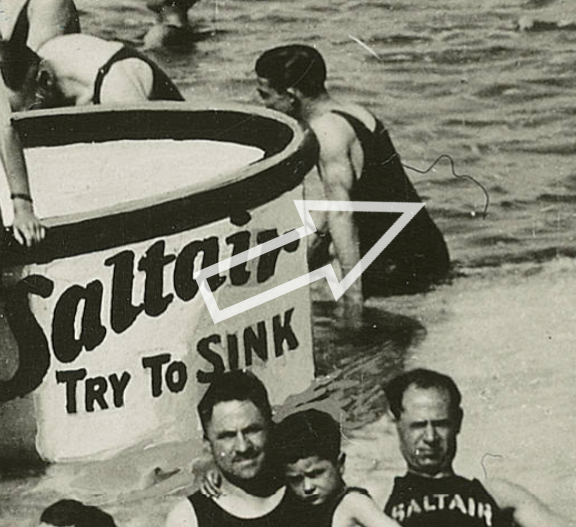

Early camera technology often could not capture the details you could see with the naked eye. As a result, subtleties in tone and texture didn’t come through when the photographer developed the film. Painting directly on the negatives or painting a printed copy of an image to bring out those lost details was also a standard photo editing practice in the early twentieth century. A few of the components in this image, including the sizable white tub in the center of the photograph, are painted over the original picture.

The designer wanted the white tub with the Saltair logo to be front and center, which meant the gentleman standing in front of the old tub in the original picture had to go. When comparing the two images, you can make out his head peeking above the tub’s back edge. Paint was then applied where his head overlapped the female swimmer’s arm, giving the soft, airbrushed illusion of a light tan line that you might never suspect was there without careful inspection. Finally, the artist painted light ripples in the water at the base to smooth and hide the harsh lines of the false white tub.

The tub’s prominence in this picture makes me suspect that the designer of this image created this composite for advertisements for the new Saltair Pavilion, which opened in 1926 after a fire destroyed its predecessor in 1925. The new pavilion provided an opportunity for the Saltair Beach Company to rebrand. The artist painted a new tub with an updated logo over the old one pictured in the original image. I believe that the designer specifically chose this particular picture because of the central location of the swimmers and the branded tub. The real-life tubs themselves were later repainted with the same Saltair brand that the artist artificially added to this image.

The artist also made other enhancements throughout the picture, including many to the stripes and trim on the pavilion. These enhancements may have been added to bring out the existing details that were lost in the development of the original photo negatives. But I suspect that these additions were made to ready the image for advertisements. The bold painted details would stand out when the agency sent the picture to be printed in low quality half-tone ads in the newspaper or brochures.

Original negatives of the final composite photograph are stored with the Utah State Historical Society and show that it was likely that prints were first created from the source negatives and spliced together on paper, then paint was applied to the newly combined images, and a final photograph was taken to create the composite image we know today. This negative would then be used to mass-produce photos as needed for various uses. Another negative of the image in the collection shows a red wash of dye applied above the pavilion, additional proof that the composite was created for advertisements. This red wash would have produced a bright white space when developed, which would allow the image to blend more seamlessly into white backgrounds, and where an advertiser could print copy up to the edge of the pavilion.

While the artist and designer of this composite spent a lot of time considering the details of the image, carefully painting over small spaces, there are a few noticeable goofs in the final edit of the composite. Including an overlapping stripe painted on the roof, drops of white paint visible on the swimmers, and tiny brush hairs left behind on the canvas.

composite image.

The origins of the composite image remain a mystery to me, and I can’t confidently say which photo company or designer created this particular image. Both the Utah State Historical Society and the special collections at the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University have copies of the print in their collections. Unfortunately, both institutions have somewhat conflicting information regarding the source and creation of the images. The original source images at the Utah State Historical Society are found in the Earl Lyman Photograph Collection and list the creator as the Utah Photo Company. The image at the Harold B Lee Library is stamped on the back “Wilson Photos 315 Tribune Bldg. Was. 4969”, but the image itself is a part of the larger Charles R. Savage Photograph Collection. I am unsure if the Wilson Photo company only produced the final negatives or if they also had a hand in designing the composite image itself. The quest for more information continues…

What I do know is that this composite is a fantastic example of early photo editing. Its legacy as one of the most shared and used images of the Great Saltair is a testament to the details and consideration paid to its visual storytelling and its advertising appeal.

Sources:

Fineman, Mia. Faking It. Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

Saltair Beach. Photograph. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. C.R. Savage Photograph Collection.

Saltair P.35. Digital image. Utah State Historical Society. Earl Lyman Collection.

Saltair P.37. Digital image. Utah State Historical Society. Earl Lyman Collection.

Saltair Beach. Photograph. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. C.R. Savage Photograph Collection.

You Float Like A Cork in the Great Salt Lake. Photograph and negative. Utah State Historical Society.

Recent Posts

ARO Spotlight: Debbie Berry from the Division of Water Rights

Utah History Day 2024: Archival Research Winners

From Pews to Pixels: Weber State’s Stewart Library Digitizes New Zion Baptist Church’s Legacy

New Finding Aids at the Archives: March 2024

Sealing the Deal: Tooele County Clerk’s Office Unlocks the Vault with Historic Marriage Records

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/