Coal Correspondence: Inspector Gomer Thomas and the 1900 Scofield Mine Disaster

This blog post was written by Jack Tingey, a 2023 Intern at the Utah State Archives and Records Service. Jack graduated from BYU with a BA in history and an emphasis on 19th century American history.

On May 1, 1900, International Workers Day, Utah State Coal Mine Inspector Gomer Thomas searched through the wreckage of the Winter Quarters No. 4 Mine, searching for survivors of a catastrophe. Several hours earlier, at 10:25 am, an explosion ripped through the No. 4 mine and into the No. 1 mine, both owned and operated by the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. Residents in the nearby town of Scofield scrambled to rescue as many miners as possible. In the weeks and months that followed, Thomas would write a series of correspondences detailing his findings on the disaster and his efforts to prevent a repeat of the horror of the Winter Quarters disaster.

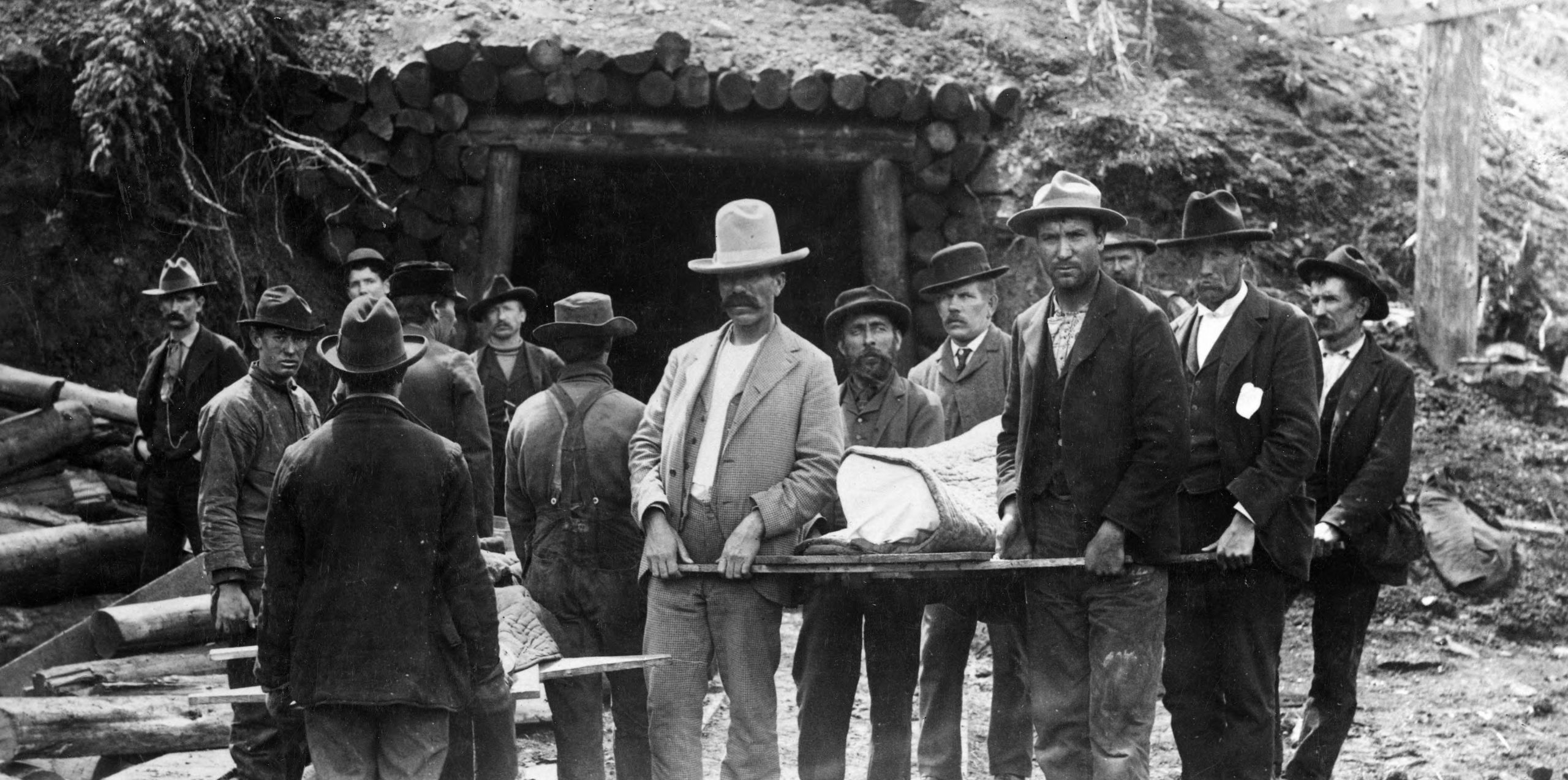

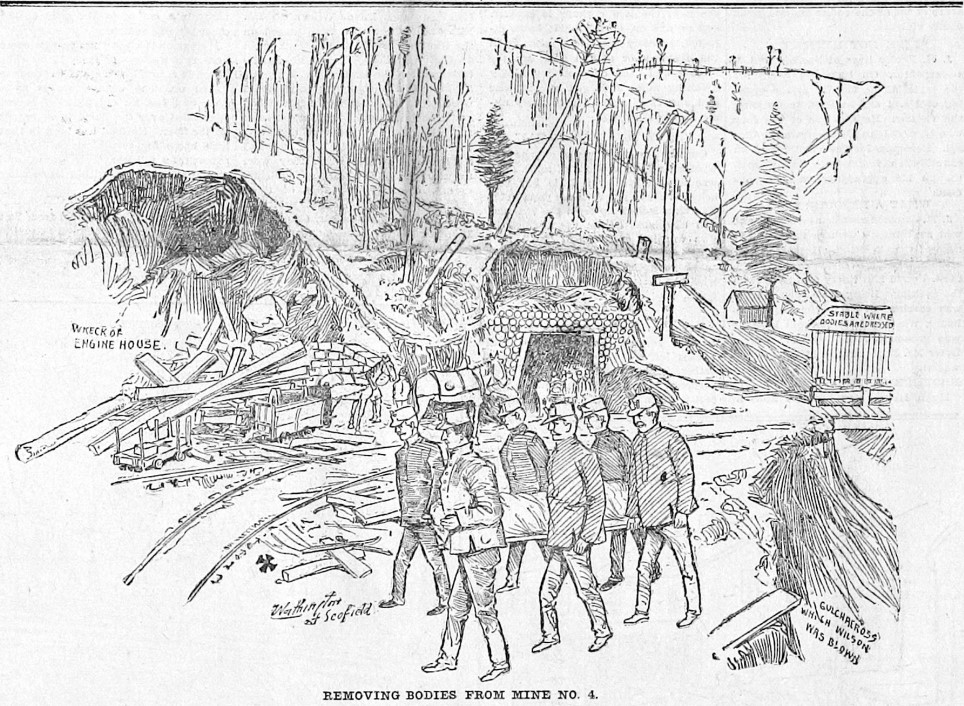

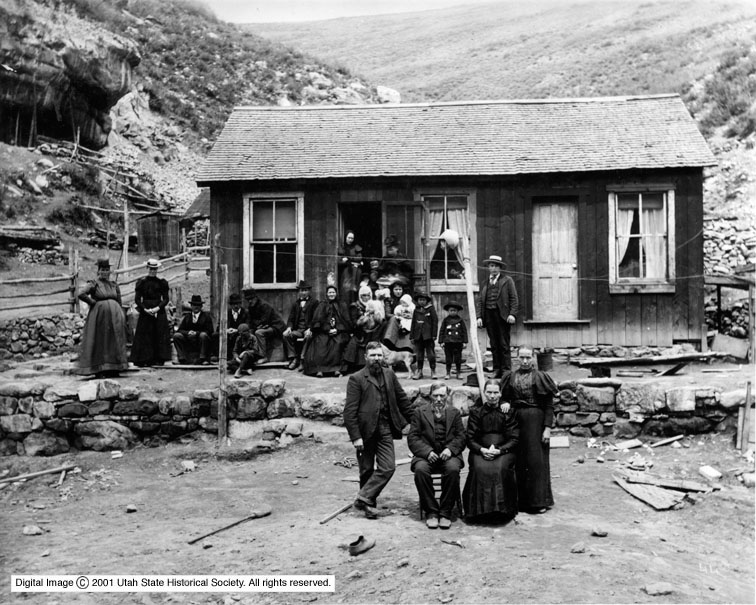

When the dust settled, rescuers began the task of counting and identifying the victims. In all, two hundred miners, according to official reports (though the number is often cited as up to 246), had been killed in moments. Many miners’ bodies had been mutilated in the explosion, which caused some confusion about the exact number of victims, along with overcrowded conditions in the mine. The poor settlements of Winter Quarters and Scofield struggled to handle the volume of bodies; there were not enough coffins for all of the deceased miners, and caskets from Salt Lake City and Denver had to be shipped in by railcar. Finally, services were held, and the over 200 victims were buried in plots in Scofield; to this day, most graves in the cemetery are from this single disaster.

The Scofield Mine Disaster was one of the deadliest accidents in American history. Families lost brothers, fathers, and husbands; the Luoma family, who immigrated to the region from Finland, lost nine male members of their family. Many Finnish and other foreign-born immigrants had settled in Winter Quarters and Scofield, and most suffered greatly after the disaster. In a twist of irony, the disaster occurred on International Workers Day, a time to celebrate the accomplishments of workers and protect their rights and safety. The damage was done, and Thomas set about investigating the cause of the disaster.

As State Coal Mine Inspector, Thomas was very concerned about the rights and safety of coal miners. Born in 1843 in Wales, Thomas had been working in coal mines for his entire adult life, including facilities in Wales, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, before eventually relocating to Utah. In 1896, Thomas was appointed State Coal Mine Inspector under Governor Heber M. Wells, to oversee safety standards at all of Utah’s coal mines. Thomas reported directly to Governor Wells, including quarterly reports on all Utah coal mines and an annual report to the Office of the Governor detailing coal mine safety conditions. Through Inspector Thomas’s correspondence, Governor Wells would have been well acquainted with safety concerns in Utah’s coal extraction facilities.

By 1900, Utah’s coal industry was thriving. Coal production had increased drastically from 1897 to 1900, increasing the demand for processed coal; thus, many mines were crewed by more workers than recommended by state regulations. Ironically, 1899 was described by Thomas as “the most successful year in the history of the coal mine industry in the State of Utah.” Over 776,000 tons of coal had been extracted, 90% of which was from Carbon County, valued at more than $908,000; amazingly, there were zero fatal accidents that year. In spite of this, Thomas still had concerns about the safety in the coal mines, one of which featured prominently in Thomas’s reports: the Winter Quarters complex.

The Winter Quarters Mines were some of the dozens of bituminous coal mines found in the Wasatch Plateau, specifically in Carbon County. The unique geology of the region, a band of mountains surrounding the San Rafael Swell, provided rich deposits of mid-grade coal at a time when the mineral was the primary fuel source for American industry. Carbon County had been created in 1894 from nearby Emery County, and dozens of towns and villages supported the coal mines. Railroad interests expanded significantly in the region, carrying coal from the mines to markets for sale. In 1903 alone, over $200,000 worth of new coal claims were registered; Carbon County’s paltry agricultural yield during the same year reflected the huge investment in coal mining and the county’s dependence on coal as its primary resource.

![Telegram from W.G. Sharp to Gomer Thomas, regarding Thomas’s request for installation of a mantrip at Winter Quarters, November 29, 1898.

(Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines. Correspondences. [Series 1283], 1898-1915.)](https://archives.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Coal-Correspondence-1-785x1024.jpg)

Years before the 1900 explosion, Thomas had expressed concern about the safety of Winter Quarters’ ventilation system and those of other mines. According to Thomas’s report from October 1897, Mine No. 1 had large amounts of combustible coal dust and too many miners working at one time. Both No. 1 and No. 4 experienced problems with proper ventilation and humidity to counter the effects of toxic gasses and coal dust. A return visit to Winter Quarters in 1899 led Thomas to declare that the mines there were safe in regards to toxic gas and that the dust was under control. Indeed, the main concern for Thomas in 1899 was the lack of a mantrip at Winter Quarters, a kind of light rail system for transporting miners into the shaft. H.G. Williams, assistant superintendent of the Pleasant Valley Coal Company at Castle Gate, corresponded with Thomas to the effect that a mantrip would shortly be installed. An April 1900 report to Governor Wells briefly mentioned further safety concerns at Winter Quarters, but the details were not mentioned, and it is difficult to know how it might have affected the accident one month later.

After the fateful events of May 1, 1900, news of the dreadful disaster spread throughout Utah. Initially, misinformation and confused reporting led the public to believe that Inspector Thomas himself was to blame for negligent inspecting, alleged by one Captain Benjamin Tibbey; Thomas denied these claims, and Tibbey later admitted to having fabricated the accusations. But the casualty figures and reports of the devastation were indeed accurate. In a private letter, Governor Wells expressed his horror at the news of the explosion. “It is a most astonishing thing to me,” Wells wrote, “that there is so wide a difference in opinion in regard to the number of men killed.” Thomas and other rescuers witnessed the mutilated corpses of the dead miners and knew firsthand the difficulty in positively identifying the number and identity of victims.

![Telegram from Heber M. Wells to Gomer Thomas, regarding confusion over discrepancies in victim count, May 7, 1900.

(Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines. Correspondences. [Series 1283], 1898-1915.)](https://archives.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Coal-Correspondence-2-784x1024.jpg)

Although speculations were brought forward in newspapers in the aftermath of the incident, Wells advised Thomas to refrain from public explanations until the inspector could conduct a formal inquiry; this report was released in June 1900. Thomas theorized that the explosion at the No. 4 mine was likely caused by volatile coal dust, which was ignited by a detonation of ten kegs of black powder. Most of the miners perished when the ventilation system, which was supposed to keep the air clear, spread whitedamp, a fatal cocktail of gasses, into nearby shafts. In effect, the explosion of coal dust in No. 4 spread toxic gas to No. 1, where most of the miners perished. Thomas concluded that the combination of dry coal dust, unreliable blasting supplies, and faulty circulation caused the accident.

![Telegram from J.S. Stillwell to Gomer Thomas regarding inquiries about smokeless blasting powder, March 22, 1901.

(Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines. Correspondences. [Series 1283], 1898-1915.)](https://archives.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/Coal-Correspondence-3-784x1024.jpg)

In the years after the disaster, Thomas held the Pleasant Valley Coal Company and other firms accountable for maintaining safety regulations. Thomas endeavored to replace the volatile materials used in the No. 4 mine, which were widespread in Utah mines, with smokeless varieties from companies in the eastern United States. Determined to prevent such an incident from reoccurring, Thomas corresponded throughout 1901 with J.S. Stillwell of New York City, a noted chemist, on the subject of “safety blasting powder” developed by Stillwell. A similar request was sent to another chemist, Fred W. Stark of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Thomas was intent on ensuring that safer materials would be available to coal miners, and in this way, he was successful. Thomas petitioned the state legislature to enact a law that would require all coal miners to evacuate a mine before setting off an explosive charge, a proposal that would not be approved until after the Castle Gate Disaster of 1924. Throughout the remainder of his tenure as State Coal Mine Inspector, Utah coal mines experienced no major accidents.

Gomer Thomas died on September 1, 1912, at the age of 68. His obituary claimed that his health had sharply declined after his role as a rescuer at Winter Quarters in 1900, likely due to the inhalation of dangerous particulates from the damaged mine. From 1896 until his retirement in 1907, Thomas had campaigned tirelessly for improved conditions for Utah’s coal mines. Thomas was fearless in using state authority to enforce safety standards for powerful coal companies, including the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. His correspondences prove his commitment to his profession and the lives of the many coal miners of Utah.

Sources Used:

- Ison, Yvette D., “The Scofield Mine Disaster in 1900 Was Utah’s Worst.” History Blazer (Jan. 1995) Via Utah History To Go.

- Donaldson, Abby, Brigham Young University. “The Scofield Mine Disaster,” Intermountain Histories, https://www.intermountainhistories.org/items/show/389.

- Parker, Dorsey Julian. “Explosions in Utah Coal Mines, 1900-1932.”. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Mines Information Circular 6752 (Nov. 1933),: 1–15.

- “Pleasant Valley Mines,” Utah Rails, Oct. 22, 2022. https://utahrails.net/utahcoal/utahcoal-pleasant-valley.php

- “Most Appalling Mine Horror!” Salt Lake Tribune, May 2, 1900.

- “Gomer Thomas Was Warned.” Salt Lake Herald Republican, May 3, 1900.

- “Thomas Declares It False.” Salt Lake Tribune, May 5, 1900.

- “Former Coal Mine Inspector Is Dead.” Salt Lake Herald Republican, September 2, 1912.

- Taniguchi, Nancy J. “An Explosive Lesson: Gomer Thomas, Safety, and the Winter Quarters Mine Disaster.” Utah Historical Quarterly 70, No. 2, 2002.

- Taniguchi, Nancy J. “Progressive Transformation: Development of Utah Coal.” Mining History Journal (1996): 22–33.

- Watt, Ronald G. “Explosion of Pleasant Valley Coal Company,” History of Carbon County, May 3, 2016.

- Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Reports, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 1268.

- Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines, Biennial Reports, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 83919.

- Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines, Reports, 1900 p. 64-112, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 23008.

- Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines, Letter Books, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 23009.

- Inspector of Coal and Hydrocarbon Mines, Correspondences, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 1283.

- Legislature, Utah Code Annotated, 1917, Vol. 1, p. 828-835, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 83238.

Recent Posts

New Finding Aids at the Archives: April 2024

ARO Spotlight: Debbie Berry from the Division of Water Rights

Utah History Day 2024: Archival Research Winners

From Pews to Pixels: Weber State’s Stewart Library Digitizes New Zion Baptist Church’s Legacy

New Finding Aids at the Archives: March 2024

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/