“All Were Rattled”: Butch Cassidy, The Castle Gate Robbery, and the Wild West

This blog post was written by Emily Stoll, a summer 2021 Intern at the Utah State Archives and Records Service. She is a senior at Weber State University and working on her public history degree.

On April 21st, 1897, the Pleasant Valley Coal Company located in Castle Gate, Utah, was robbed in broad daylight. Considered to be one of the most audacious hold-ups that occurred in the Western frontier, the Castle Gate crime was committed by the notorious outlaw Butch Cassidy. Cassidy, with help from Wild Bunch outlaw gang member Elzy Lay, stole a bag of silver coins valued at around $1,000 from the Pleasant Valley Coal Company according to the court records available in the Utah State Archives. The true story of the robbery varies from account to account and has entered into its own place amidst Utah legends.

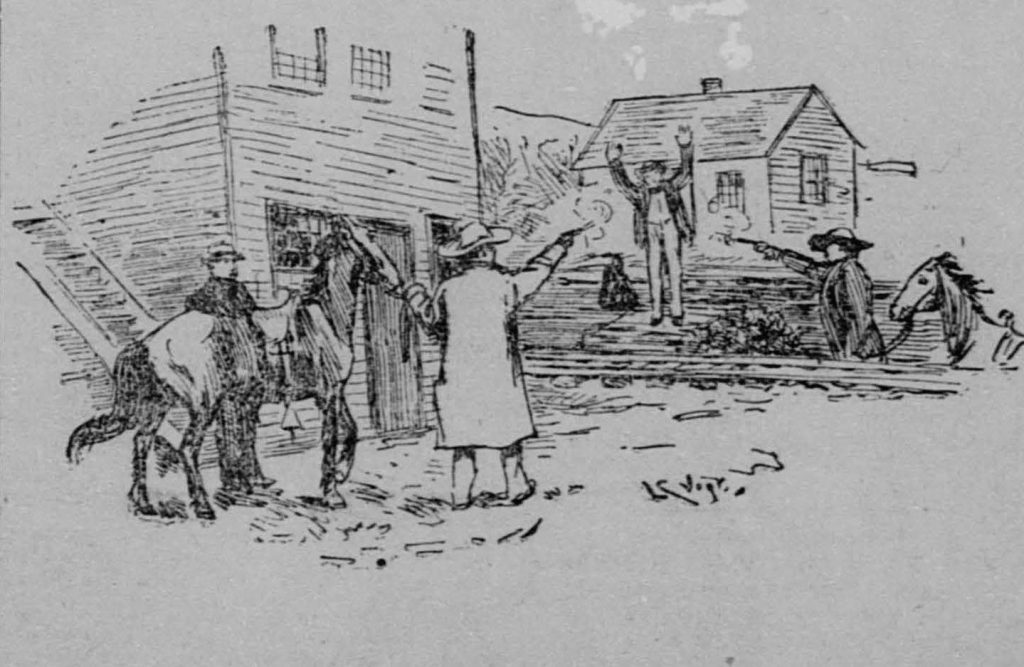

A newspaper article published in the Salt Lake Herald from the day after the robbery provides a detailed account of the event from witness E.L. Carpenter, the cashier for the Pleasant Valley Coal Company. Carpenter, colorfully described as “as plucky a little man as walks,” along with his wife were well-known residents of Salt Lake City, the article noted. According to the paper, Cassidy and Lay waited outside of the main building of the Pleasant Valley Coal Company beneath the stairs that led up into a higher entrance of the building. The outlaws soon confronted Carpenter and another employee, ordering the workers to “Drop them sacks … and hold up your hands.” Once the money had been handed over, one of the outlaws began “whirling a sixshooter in his hand and firing shots promiscuously to create consternation.”

The retreating outlaws fled towards the Halfway House and began to cut telegraph wires, as they moved throughout Price and Helper. However one of the lines was cut too late as the local sheriff, Sheriff Donant, “hastily gathered a posse of four men” to follow the outlaws. The robbers were lucky to escape that day, but the effects of this crime would shock all of Utah and the West, with even a newspaper in Sacramento, California reporting the crime, calling it a “daring robbery.”

According to the 1880 Federal census, Cassidy was born Robert LeRoy Parker in Beaver, Utah to his English immigrant parents Maximillian and Ann Campbell Gillies. He spent his early years working as a rancher across western Utah, which occasionally included minor thefts of cattle and ranching equipment to support himself.

His familiarity with the Utah landscape was key to most of his getaways. The infamous Robber’s Roost Canyon in southeastern Utah served as the perfect hideout for the Wild Bunch as the difficult terrain concealed the hideout from unfriendly travelers. Cassidy also made use of the Outlaw Trail, named in later years for the secret hideouts and canyons that carved through the west from Montana to Mexico. The Outlaw Trail connected Robber’s Roost to a large network that was well-known by outlaws for its local communities on the edge of civilization which welcomed them as they passed through. It was this trail that Cassidy and Lay would use to make their escape from Castle Gate.

Throughout the years, several newspapers have reprinted archived stories commemorating the event of the Castle Gate Robbery, each with its own twist on the reporting of the crime.

In an article from The Helper Journal in 1973, the author claims that during their escape, Lay and Cassidy “gave an impromptu demonstration of horsemanship rodeo style for the 100 or so openmouthed witnesses” as well as a shootout straight from a movie that involved “Carpenter being robbed and chasing outlaws around in his bedroom slippers, and continued with Butch Cassidy, loot in hand, chasing his horse around Castle Gate.”

In another article from Susan Spano in the Los Angeles Times, Spano claimed that E.L. Carpenter chased the robbers “in a locomotive detached from the rest of its train.” The article also contains a short interview with Alfred Fullmer who claimed that he “raced horses with the Parker boys” and might have even met the outlaw himself during his youth in Circleville. Small claims and interviews like this are common when doing research into the life of Butch Cassidy, with locals often claiming that they had a grandfather or distant relative who told stories about interacting with a legendary Western outlaw.

Another example of this is found in an article written for the Dialogue Journal by Edward Geary, a former professor at Brigham Young University. In his article, “The Girl Who Danced With Butch Cassidy,” Geary touches on his childhood in a small town close to Castle Gate, including his neighbor named Retty Mott who reportedly danced with Butch Cassidy at a local dance. Geary mentions that, “Down to my own day the boys of Helaman played Robbers Roost Gang, riding their horses helter-skelter out of a hundred Castle Gates in every hollow of the dry hills.” He also includes references to the town myth that Butch Cassidy and his accomplices sheltered the winter of 1896 at the Mott homestead, reportedly planning their daring crime.

While the days of gunslingers, outlaws, and frontier justice are long gone, stories like this help preserve the romantic idea of the “Wild West.” Well-documented legends such as the Castle Gate robbery are essential stories that provide insight into frontier communities in areas like Carbon County and paint the American West as a land of adventure, opportunity, and excitement. Oftentimes these stories and incidents of crime and disaster are some of the only historic ties that exist to connect small communities to larger movements and eras in the past. It is common for people to cling to their distant ties to a certain historical event or era. A personal connection to a historic moment can be a large motivator for anyone to gain a sense of their past, and can encourage others to revisit their local history. Delving through the digital record collections present in the Utah State Archives, as well as the Utah Digital Newspaper archives, the story of the Castle Gate robbery contributed greatly to the idea of the “Western mythos” or romanticism. While the factual evidence of E.L. Carpenter’s account was likely embellished, it is the repetition of the story in its multiple fantastical versions that has made it so important to the history of local communities that stand as a reminder of Utah’s past in rollicking history of the American West.

Butch Cassidy was certainly a complex individual that greatly contributed not only to the history of Utah, but to a unique historical perspective regarding the development of the western United States that still lingers to this day. Take a trip yourself into Utah’s rich history and colorful past at the Utah Digital Archives website—who knows what your research will discover!

Sources Used:

“Daring Robbery at Castle Gate, Utah.” Sacramento Daily Union, April 22, 1897.

“Desperados at Castle Gate.” Salt Lake Herald, April 22nd, 1897.

Geary, Edward. “The Girl Who Danced With Butch Cassidy.” Dialogue: A Journal Of Mormon Thought 11, no. 3 (Autumn 1973):139-43. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45224714.

Hunt, Joan. “Desperadoes grab payroll at Castle Gate Depot.” The Helper Journal, April 26th, 1973.

“Rounding up Outlaws in the Colorado Basin.” The San Francisco Call. April 3, 1898. From the Library of Congress. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1898-04-03/ed-1/seq-20/.

Spano, Susan. “The Local Story of Butch Cassidy.” Los Angeles Times reprinted in the Daily Herald, May 2nd, 2008.

“History of Butch Cassidy, LeRoy Parker.” Utah.com. Accessed July 17, 2021. https://utah.com/old-west/butch-cassidy.

Photographs and images used:

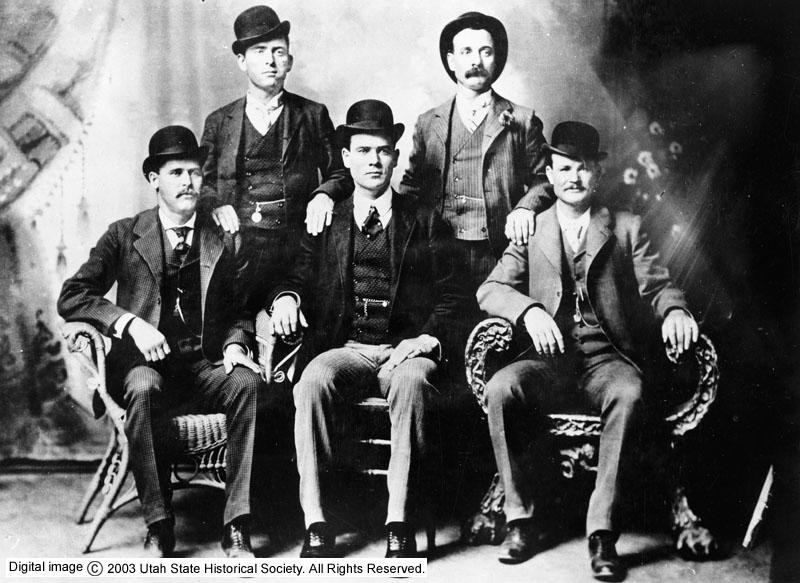

“Butch Cassidy and the ‘Wild Bunch’” 1900. Utah State Historical Society Classified Photo Collection, Utah State Historical Society. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6183dwb.

“Parker Ranch in Circleville” 1990. G. E. Keeney collection, Uintah County Library. Evanston, WY. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6c85q8v.

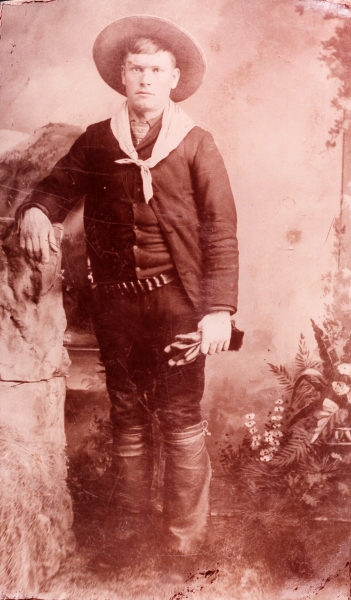

“Butch Cassidy of the Wild Bunch” January 1st, 2004. Uintah County Library Regional History Center. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6xh34v2.

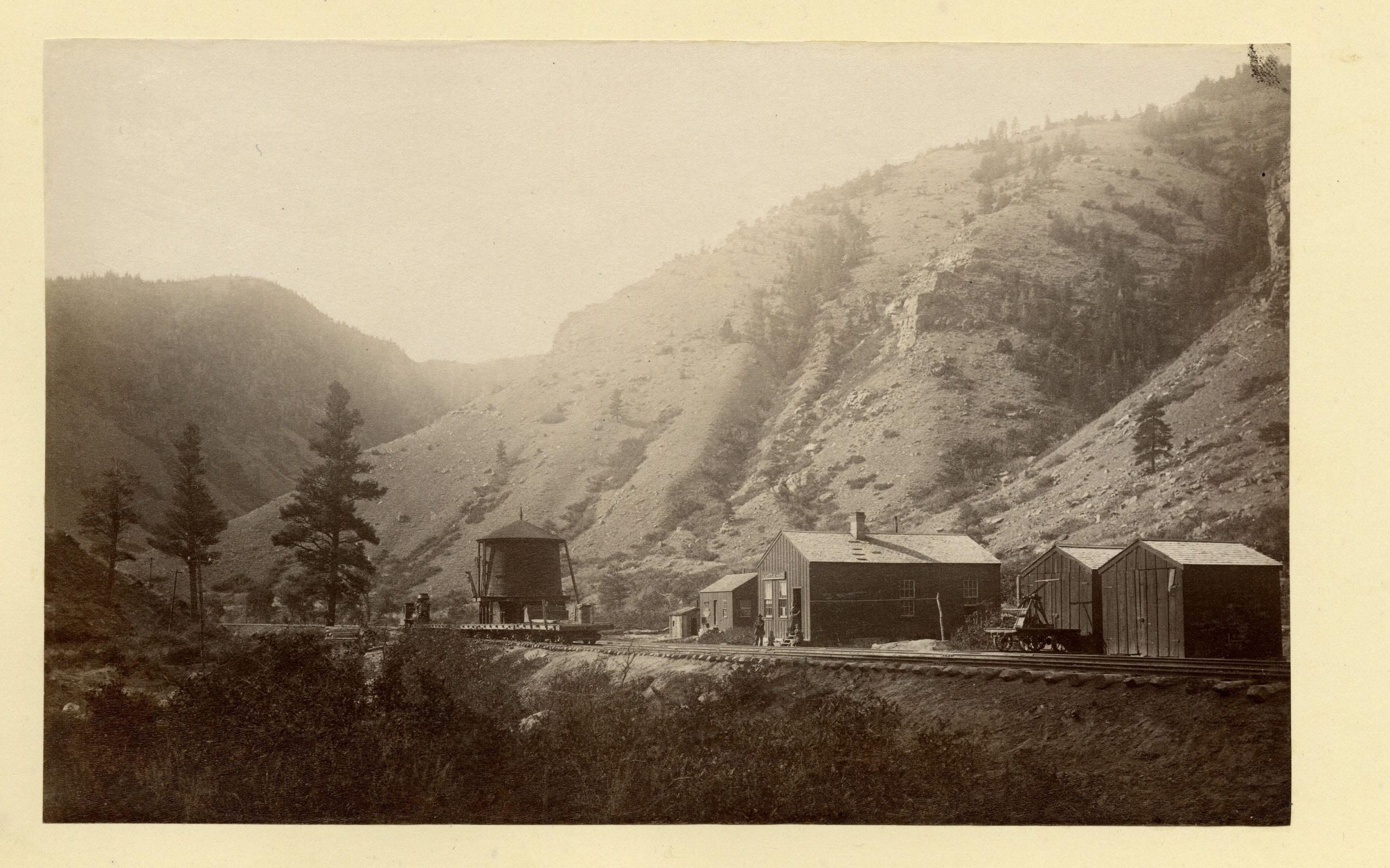

Soule, John P. “Castle Gate Station” 1883. John P. Soule Photograph Collection. Castle Gate, Utah. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6dc3h8z.

Drawings from Salt Lake Herald, “Desperadoes at Castle Gate” April 22nd, 1897. No artist is listed, nor is there an author for the article. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6pp0cr1/11442315.

“Cassidy, Butch-Cabin P.1” April 10th, 2009. Classified Photograph Collection, Utah State Historical Society. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6np2jmr.

Indictment of Grand Jury. 1897. Series 4031, District Court (Seventh District: Carbon County), Criminal case files, The State of Utah against Butch Cassidy, Utah State Archives. https://images.archives.utah.gov/digital/collection/p17010coll29/id/21

Recent Posts

New Finding Aids at the Archives: April 2024

ARO Spotlight: Debbie Berry from the Division of Water Rights

Utah History Day 2024: Archival Research Winners

From Pews to Pixels: Weber State’s Stewart Library Digitizes New Zion Baptist Church’s Legacy

New Finding Aids at the Archives: March 2024

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/