Eugenics in Twentieth-Century Utah

This blog post was written by Jack Tingey, a 2021 Intern at the Utah State Archives and Records Service. Jack graduated from BYU with a BA in history and an emphasis on 19th century American history.

In the spring of 1927, Esau Walton awaited forced sterilization under Utah’s eugenics laws. In May of that year, the state corrections board had ruled that Walton must be sterilized, under the recommendation of Utah State Prison warden R.E. Davis. Walton was Black and, according to the case, an accused “homosexual.” Thus, he fell into the guidelines of the sterilization laws of Utah, which gave the state authority to sterilize individuals deemed unfit to reproduce. The case of Esau Walton represents a well-detailed example of the impact of eugenics in Utah, but he was among hundreds of Utahns who faced sterilization and institutionalization in the name of “intelligent modernity.”

The modern iteration of eugenics began in the eighteenth century in England, and the philosophy later became popular in the United States. At its core, eugenics championed the sterilization of mentally and physically defective persons to ensure those “undesirable” traits would not be passed onto future generations. Automobile industrialist Henry Ford expressed sympathy for eugenics; inventor Alexander Graham Bell was the chairman of the board for the Eugenics Records Office, established in 1910. By the early twentieth century, the principles of eugenics had gained influential proponents, and US states began to write these principles into law.

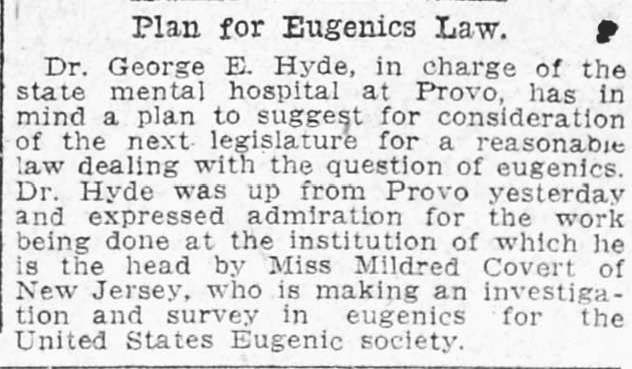

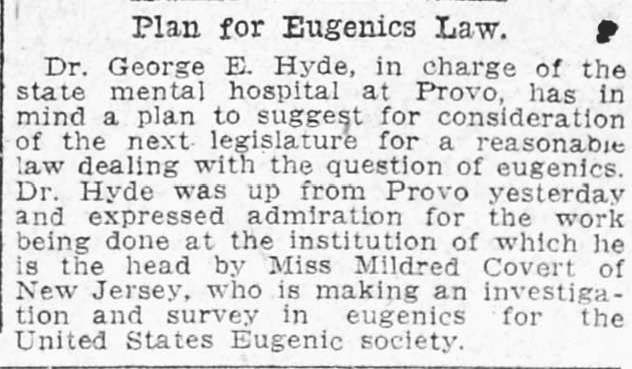

Utah was the 23rd state in the Union to pass eugenics-inspired laws. The first eugenics organization in Utah, the Utah Eugenics Society, was founded in April 1914, with Frank M. Driggs as president. The group lobbied for eugenics laws to be passed in Utah, as had been done in Indiana and other states. Although some in Utah opposed the adoption of eugenics laws, the Utah legislature approved a bill in March 1925. Under these laws, “habitual sexual criminals, idiots, epileptics, imbeciles, and the insane” were considered unfit to reproduce and, therefore, a harm and burden to society.

Little is known about Walton’s personal life from the records, other than that he served 15 months in a Georgia juvenile detention center for theft as a child, and had committed other crimes through his adolescent years. Walton first arrived in Utah in 1923 at the age of 17, shortly after the death of his mother in Georgia. At the time of his trial, he had only completed a fourth grade education. His motivations for moving to Utah are unknown, but within two years of residing in Utah, Walton once again found himself in trouble with the law.

Walton entered the Utah State Prison in Sugar House on November 5, 1925, after being convicted of robbery. While incarcerated, witnesses alleged that Walton engaged in “the act of sodomy,” which convinced Warden R.E. Davis that Walton should not be able to procreate, ostensibly for the betterment of American society. Davis recommended to a special state board order that Walton be sterilized, a decision the board approved in May 1927. However, the provisions of Utah’s eugenics law stipulated that the subject held the right for appeal. Walton chose to appeal to the District Court in Salt Lake City, represented by Parley P. Jenson, a local Utah lawyer. Davis and the State Board of Corrections were represented by the Utah Attorney General himself, George P. Parker.

Walton and the defense argued that the order of sterilization from the special board was unconstitutional, and at the very least that Walton did not meet the requirements for sterilization. The respondent, Warden Davis and his counsel, produced a witness to Walton’s alleged sexual crimes. This witness was a guard at the prison in Sugar House, who claimed that he saw Walton and another inmate engaged in homosexual intercourse. Attorney General Parker brought a Dr. S.H. Besley to testify of the medical need for the procedure; Dr. Besley claimed that Walton’s general health would not be affected by the procedure, merely that his ability to reproduce would be neutralized.

The court listened to witness testimonies and arguments until the case was decided on April 9th, 1929. The court ruled that forced sterilization was indeed constitutional, but that in Esau Walton’s case, sterilization would not affect any supposed condition. Because of this ruling, Walton escaped sterilization, but the constitutionality of the law allowed the state to continue eugenics programs until the practice of sterilization for most conditions ended in Utah in 1963. Technically, the law still allows for the sterilization of persons with disabilities according to Chapter 6 of Utah Code 62A.

Esau Walton was only one of hundreds of individuals considered for sterilization in the state of Utah. By 1963, 772 people had been forcibly sterilized under Utah’s laws regarding eugenics. Sterilizations were performed at the Utah State Hospital, a substantial brick building in Provo. Medical staff at the hospital would conduct procedures to neutralize reproductive capability for the patient, male or female. These patients were, in reality, victims of life altering surgeries against their will. Aside from Esau Walton, very few sterilization victims ever had their cases reviewed or disputed. The law stated that any individual recommended for sterilization reserved the right to legal counsel, and the right to appeal the decision to sterilize. However, the majority of sterilization orders were upheld and the accused underwent the procedure regardless.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest religious denomination in Utah, held no official position on eugenics, though many leaders in the church did offer opinions. B.H. Roberts, a church historian and noted intellectual, compared his church’s practice of plural marriage with the favorable aspects of eugenics. One eugenicist, not a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, made similar comparisons, noting the practice of vetting prospective spouses for desirable physical qualities. An 1888 law passed in Utah prohibited miscegenation, or mixed race marriages, which was in line with eugenics principles of discouraging white individuals from marrying outside their race. The church made an official statement in 1909 on the origin of the earth, but made no mention of the evolution of man; other leaders in the church, such as Apostle Anthony Ivins, supported eugenics practices. There was no official prohibition or discouragement of eugenics on the part of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, meaning eugenics was not officially opposed.

At the time of Walton’s case in the late 1920s, the law of Utah recommended sterilization for “…persons afflicted with habitual sexual criminal tendencies, insanity, idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness, and epilepsy, who are confined in the Utah state hospital and sanatorium, the state industrial school, and the state prison.” The law prohibited homosexual acts, which could be punished by three to twenty years in state prison. Medical experts in Utah considered homosexuality itself to be a mental illness, an opinion not officially amended in the law until 1973. The justices on the Utah Supreme Court referred to homosexuality in the harshest language, labeling homosexual acts as “revolting” and “degenerate,” reflecting public opinion at the time. But Utah accounted for only a small part of the legacy of eugenics.

The state of California led the nation in sterilization, reporting over 20,000 such procedures before the practice ended in 1964. The state adopted eugenics laws in 1909, one of the first states to do so. The actions of California medical staff influenced others, including top Nazi scientists. As early as 1933, Germany enacted laws that called for the sterilization of individuals considered unfit with the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring; American supporters of eugenics championed the move. These laws created precedent for the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which were used to create the framework for the network of Nazi death camps, leading to the deaths of millions of people, especially Jews, Romani, homosexuals, disabled persons, and other groups considered inferior. The eugenics movement as a whole lost credibility after the end of World War II, as the movement became associated with the atrocities of the Nazis.

The legacy of eugenics in Utah, and in the rest of the United States, remains one of tragedy and suffering. Most of the victims were women, many had mental illness or physical disability, and almost all of them were poor. The case of Esau Walton demonstrates to a modern audience the horror of racist, homophobic policies and their consequences. This story is only a small portion of the many examples of medical crimes committed by state and federal institutions. Among Indigenous Americans, at least 25 percent and as many of 40 percent of Indigenous women were forcibly sterilized by federal officials during the 1970s. While today historians are still counting the numbers and compiling the experiences of the victims, the legacy of eugenics continues to be a dark chapter in the history of Utah, and the United States.

Sources Used:

Elias Hansen, J., and J. Straup. “Davis, Warden v. Walton.” CaseText. Casetext, Inc., n.d. https://casetext.com/case/davis-warden-v-walton.

Salt Lake Herald-Republican. “Eugenics at its Acme”, February 8, 1913. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6zs42cd/10105089.

“Ford’s Anti-Semitism – American Experience.” PBS WGBG. PBS, 2012. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/henryford-antisemitism/.

Eugenic Archives – Eugenics Record Office. Truman State University, 2004. http://eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/static/images/971.html.

“Utah, 23rd State to Pass Sexual Sterilization Legislation.” The Eugenics Archives. Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, n.d. https://eugenicsarchives.ca/discover/timeline/53233e96132156674b000241.

Salt Lake Telegram. “Driggs is Elected Society’s Head,” April 4, 1914. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s66q354m/15903685.

Ordover, Nancy. American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. pp 80.

Engs, Ruth Clifford. The Eugenics Movement: An Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2005.

Stuart, Joseph R. “‘Our Religion Is Not Hostile to Real Science’: Evolution, Eugenics, and Race/Religion- Making in Mormonism’s First Century.” Journal of Mormon History 42, no. 1 (January 2016): 1–43.

Kaelber, Lutz. “American Eugenics.” Eugenics: Compulsory Sterilization in 50 American States. University of Vermont, n.d. http://www.uvm.edu/~lkaelber/eugenics/.

Ivins, Anthony W. Her Mother’s Daughter. Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1931.

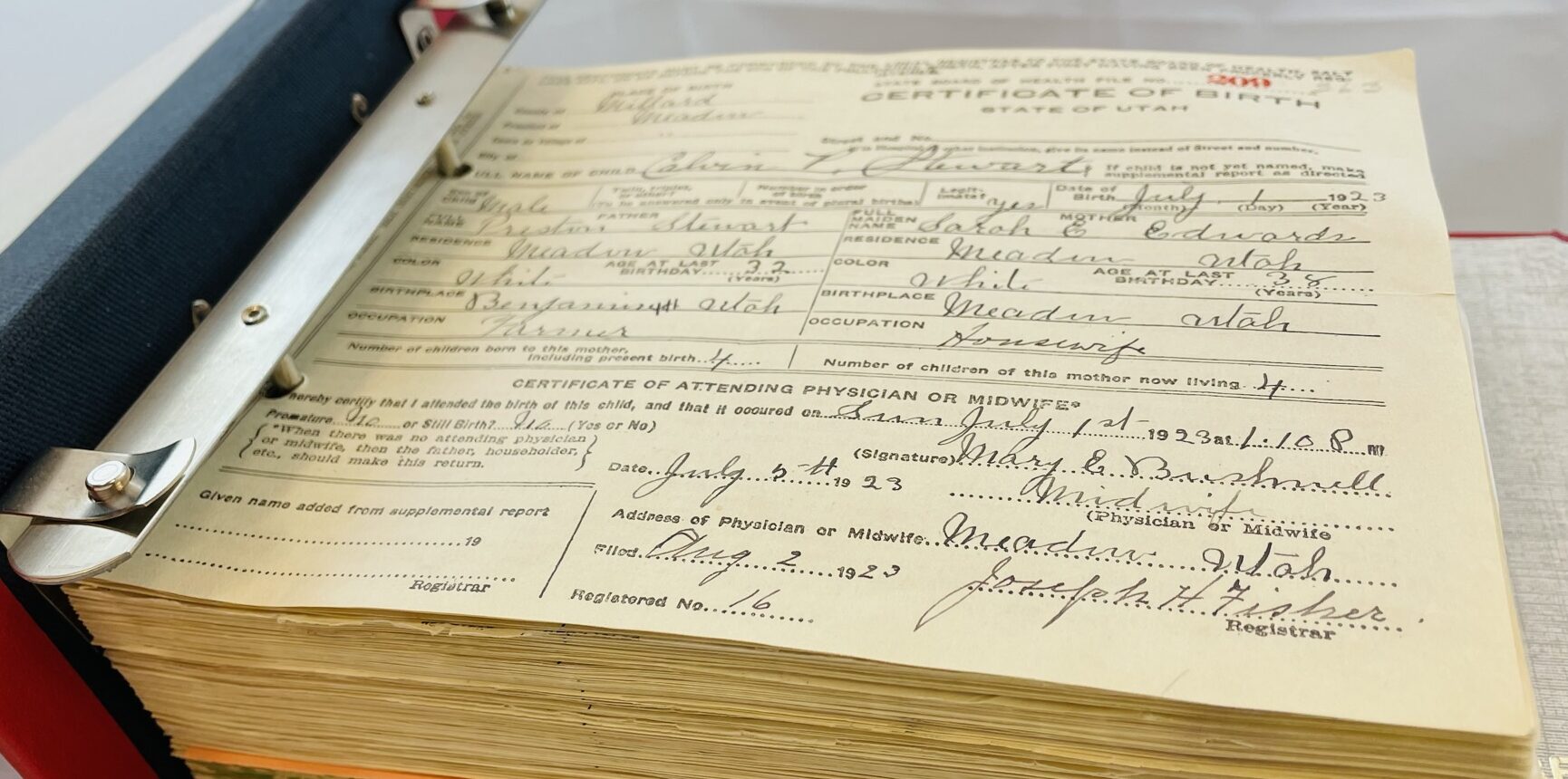

Laws of Utah 1923, ch. 13, enacted Feb. 17, 1923.

Peterson, Maren. “Women in the LGBTQIA+ Community: Stories of Utah Women.” Utah State Archives and Records Service. State of Utah, August 18, 2020. http://69.169.175.38/archives-news-local/2020/06/30/women-in-the-lgbtqia-community-stories-of-utah-women/.

Black, Edwin. “Eugenics and the Nazis — the California Connection.” San Francisco Chronicle, November 3, 2003.

“The Biological State: Nazi Racial Hygiene, 1933–1939.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, n.d. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-biological-state-nazi-racial-hygiene-1933-1939.

Ralstin-Lewis, D. Marie. “The Continuing Struggle against Genocide: Indigenous Women’s Reproductive Rights.” Wicazo Sa Review 20, no. 1 (2005): 71-95. doi:10.1353/wic.2005.0012.

Photographs and images used:

“Utah State Prison from Northwest” 1903. Utah State Historical Society Shipler Commercial Photographers Collection, Utah State Historical Society. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6280k2t.

“Utah State Hospital-Provo P.2”. Utah State Historical Society Classified Photographers Collection, Utah State Historical Society. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6x92r8f.

Salt Lake Tribune, “Plan for Eugenics Law” January 23, 1918. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6ft9xgp/14945502.

Recent Posts

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/