The Law of the River: The Central Utah Project

This is the third (and final) in a series of blog posts that will explore records held by the Utah State Archives that help illuminate the story of Utah’s role in the larger western movement to tame and develop the Colorado River as a vital resource in the arid west.

ENVISIONING THE CENTRAL UTAH PROJECT

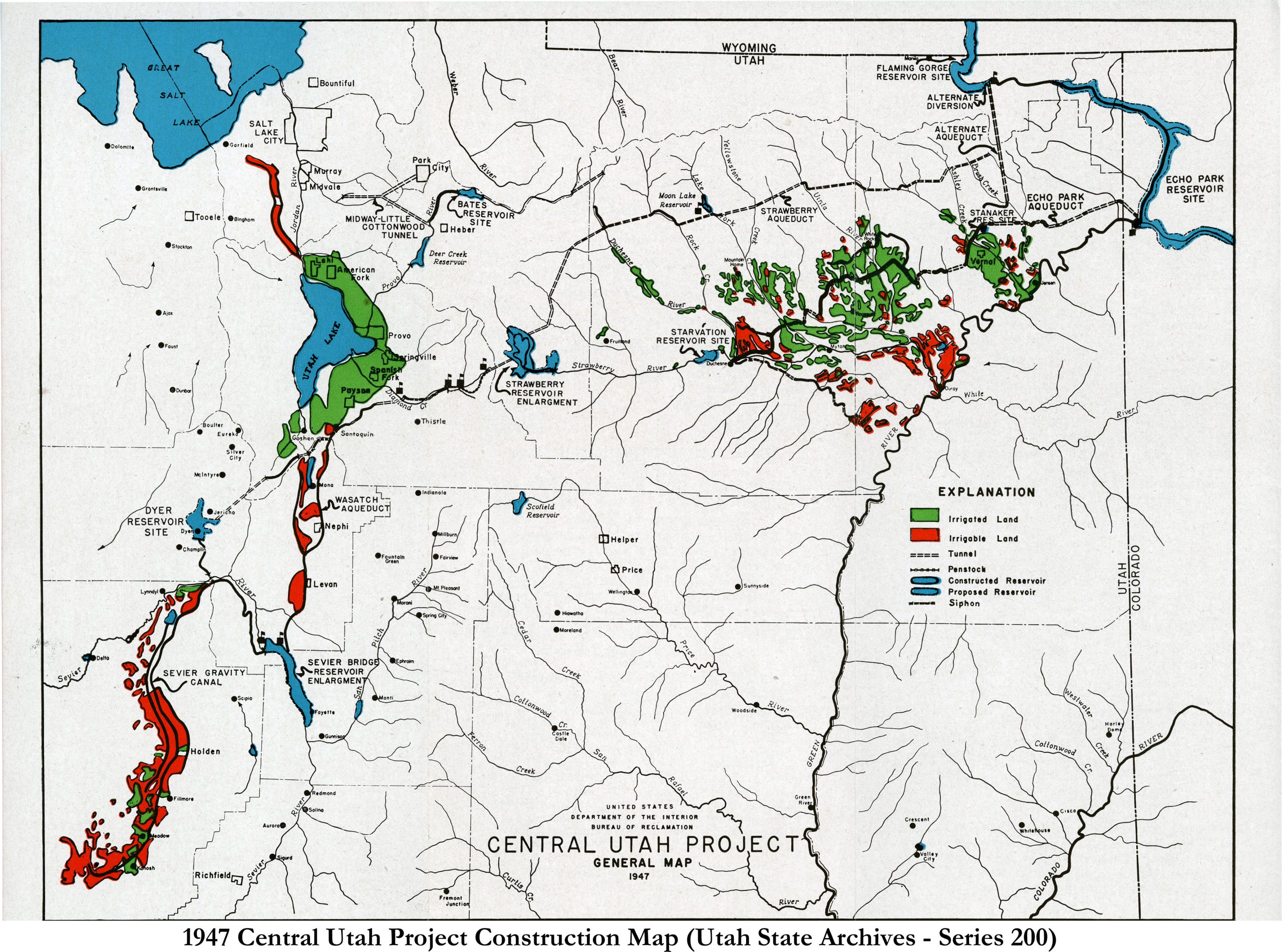

Due to circumstances of geology and demographics, the bulk of Utah’s population lives on the eastern edge of the Great Basin, hundreds of miles (and thousands of feet of elevation) removed from the Colorado River water promised to the state by the Colorado River Compact. In 1946 the first scheme for addressing this disconnect was conceived. Modeled on successes by the Bureau of Reclamation in the early 20th century at Utah’s Strawberry Reservoir and nearby Heber Valley, local planners developed the concept of the Central Utah Project (CUP).

According to its proponents, the CUP would guarantee full use of Utah’s allotted share of the Colorado River by implementing a series of aqueducts, diversion and storage dams, and tunnels that would effectively move water from the eastern Colorado River Basin to other areas of the state, including the growing population centers along the Wasatch Front.

The first attempt to create the CUP came in 1946 when federal legislation was proposed by Utah senator, Abe Murdock. This legislation was met with defeat, as it was determined that any attempt at such a massive project in Utah needed to be bound up with larger planning in the Upper Colorado River Basin as a whole. Up to that point, the states of the Upper Basin hadn’t even determined how the Upper Basin allotment would be divided between them. This, in turn, spurred negotiations that would lead to the 1948 Upper Colorado Basin Compact, an agreement that granted Utah 23% of the 7,500,000 acre feet of water apportioned to the Upper Basin by the Colorado River Compact.

In that same year (1948), the Colorado River Storage Project Act (CRSPA) was also proposed. This legislative action proposed a comprehensive plan for developing the Upper Colorado River Basin. However, a variety of delay’s prevented the Congress from authorizing it until 1956. Upon its authorization, the Central Utah Project was born, effectively serving as the largest single participating unit in the CRSPA plan.

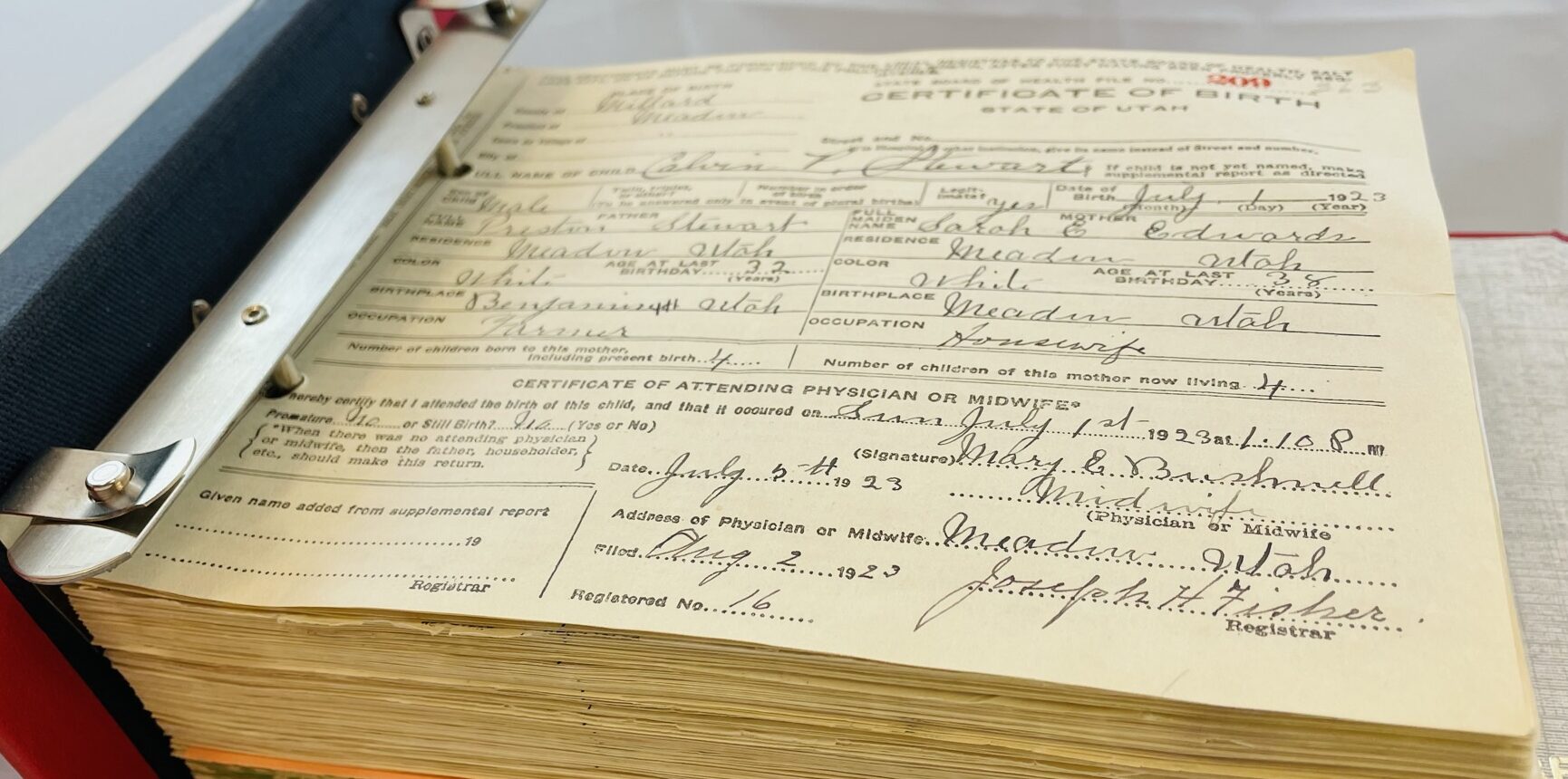

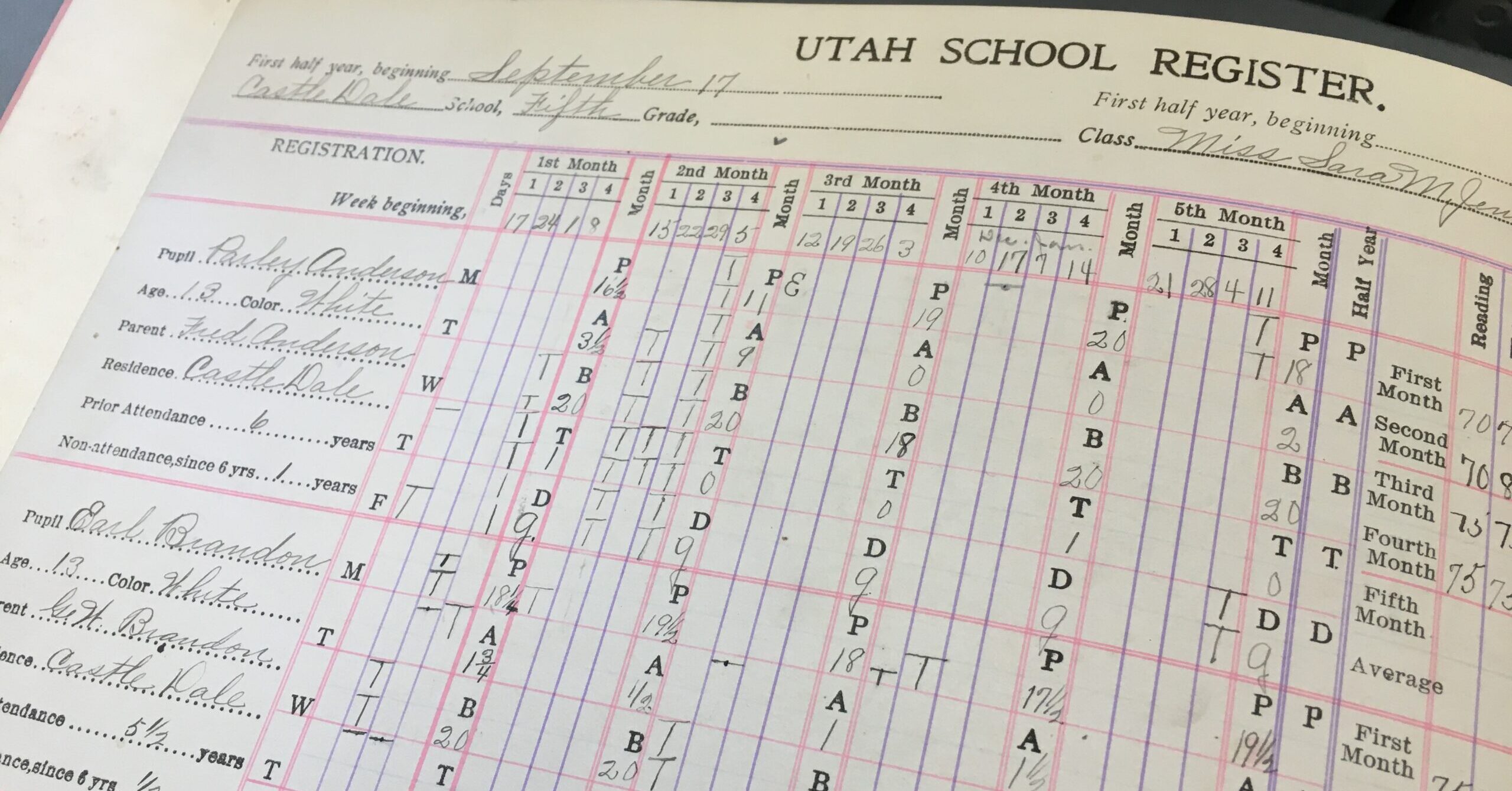

This early history of the CUP’s origination and initial planning is reflected in records held by the Utah State Archives, which includes correspondence records from the office of Utah Governor J. Bracken Lee (1946-1956), as well as Colorado River Commission case files created by the Utah Attorney General.

CUP ORGANIZATION

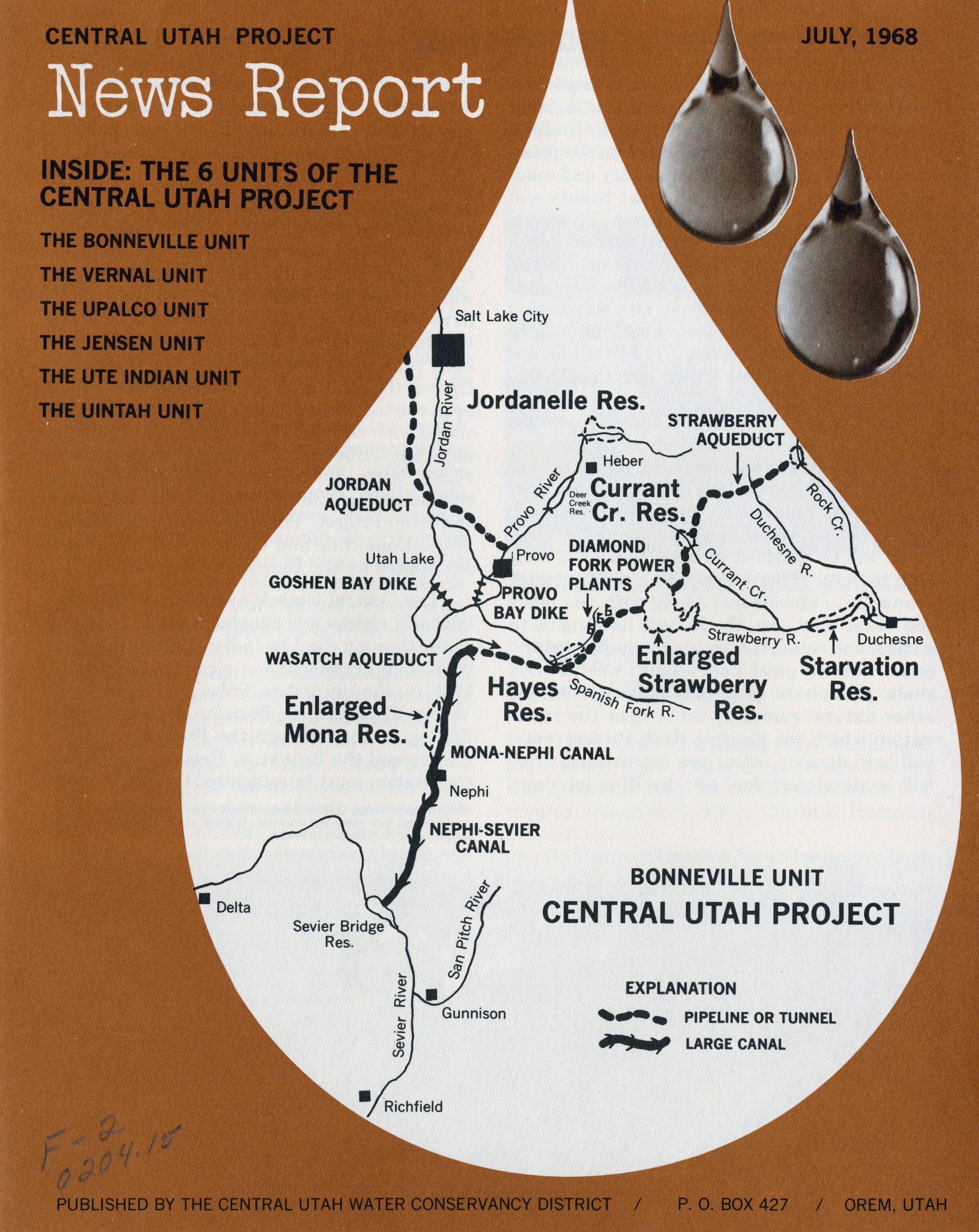

In simplest terms, the CUP serves to build the infrastructure needed to impound and transport water from the eastern Utah river basin to other water-starved regions in America’s second most arid state. The organizational apparatus for developing the CUP water delivery systems was born in 1964, with the legal organization of the Central Utah Water Conservancy District (CUWCD). The original seven-member board of the CUWCD was composed of one representative from each county in Utah impacted by CUP projects. This original board included members from the counties of Salt Lake, Summit, Wasatch, Utah, Juab, Uintah, and Duchesne. Later the board would expand to include representation from Garfield, Piute, and Sanpete counties. The CUWCD was established to both oversee the management of water projects associated with the CUP, as well as manage Utah’s repayment of federal funds that had been allocated for CUP projects by the Colorado River Storage Project Act.

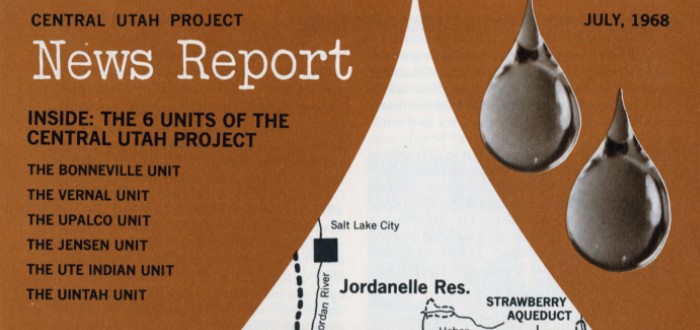

The CUWCD set to work by first organizing water development projects around the state into seven distinct geographic units: Vernal, Upalco, Jensen, Bonneville, Uinta, and Ute Indian. Setting project priorities and allocating resources has often proved contentious, particularly as projects went over time and budget throughout the latter 20th century. For example, in 1965 the Bonneville Unit (the single largest unit of the CUP) was allotted $302 million in funds to complete its associated water projects. Construction delays and the passage of time meant that, by 1985, over $2 billion in funds had actually been spent developing the Bonneville Unit.

The early history of work done for the CUP, as well as ongoing debates of how to fund the project appear throughout several record series held by the Utah State Archives. These include Upper Colorado River project files from the office of Governor George D. Clyde (1957-1965), correspondence records from the office of Governor Calvin Rampton (1965-1977), natural resource working files from the office of Utah Governor Scott Matheson (1977-1985), and correspondence records from Governor Matheson’s office.

COMPLETING THE CUP

Over time it became increasingly clear that the broad, ambitious goals of the CUP would be bogged down by both slow construction, as well as a lack of adequate ongoing funding and support from the federal government. Funding for the CUP (through the Bureau of Reclamation) was often a contentious point of debate among federal lawmakers, and the entire project was nearly defunded completely during the term of President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981).

The tendency to stall or delay water projects ultimately led to an unprecedented action in 1992, when Utah’s state and local officials asked the federal government to turn over authority to complete all unfinished CUP work to the CUWCD. This request was granted with passage of the 1992 Central Utah Project Completion Act (CUPCA). This legislation authorizes the CUWCD to oversee completion of CUP projects, particularly those in the Bonneville unit which includes areas of exploding population growth along the Wasatch Front. In addition, the legislation provides a means for over-site and environmental mitigation of CUP work to be overseen by the U.S. Department of the Interior through a newly created CUPCA office.

This climactic moment in the CUP’s history, as well as the negotiations that took place to secure passage of the CUPCA, can be traced in records held by the Utah State Archives, including Governor Norman Bangerter’s Washington Office records, as well as Governor Bangerter’s Chief of Staff correspondence records.

UNKNOWN FUTURES

The future of the Colorado River, and its millions of users, is a hazy one. How reliable will the river’s flow remain, particularly in the face of changing environmental conditions and exploding population centers in the western United States? Water allocations from the Colorado River have been re-calibrated at points in the past, based on lower flows and the fact that the original numbers agreed to in the 1922 Colorado River Compact were based on unusually (and unsustainable) high years of river flow.

A similarly unknown future faces the major water storage projects along the river, including those that compose the Central Utah Project. Consider, for example, the unknown fate of the Hoover Dam, an aging structure holding back a dwindling water supply that is currently being drawn on by more people than at any other point in its history.

Major questions concerning the Colorado River, and its use, face each of the western states that rely heavily on its water. Will the answer be a doubling down on the types of costly reclamation efforts that were meant to help the arid southwest “bloom like a rose?” Or will the answers increasingly take the shape of users learning how to more efficiently utilize the regions most critical resource? Whatever way the future flows, it is clear that the Law of the River is still, very much, a work in progress.

- Bureau of Reclamation/

- Central Utah Project/

- Colorado River/

- Colorado River Commission/

- Duchesne County/

- Garfield County/

- Governor Calvin Rampton/

- Governor George D. Clyde/

- Governor J. Bracken Lee/

- Governor Norman Bangerter/

- Governor Scott Matheson/

- Jensen Unit/

- Juab County/

- Piute County/

- Salt Lake County/

- Sanpete County/

- Summit County/

- Uintah County/

- Utah County/

- Wasatch County/

Recent Posts

Authors

Categories

- Digital Archives/

- Electronic Records/

- Finding Aids/

- General Retention Schedules/

- GRAMA/

- Guidelines/

- History/

- Legislative Updates/

- News and Events/

- Open Government/

- Records Access/

- Records Management/

- Records Officer Spotlights/

- Research/

- Research Guides/

- State Records Committee/

- Training/

- Uncategorized/

- Utah State Historical Records Advisory Board/